Mathematics is full of surprising connections between two seemingly unrelated topics. It’s one of the things I like most about maths. Over the next few blog posts I hope to explain one such connection which I’ve been thinking about a lot recently.

The Stone-Čech compactification connects the study of C*-algebras with topology. This first blog post will set the scene by explaining the topological notion of a compactification. In the next blog post, I’ll define and discuss C*-algebras and we’ll see how they can be used to study compactifications. In the final post we will look at a particular example.

Compactifications

Let \(X\) be a locally compact Hausdorff space. A compactification of \(X\) is a compact Hausdorff space \(K\) and a continuous function \(\phi : X \rightarrow K\) such that \(\phi\) is a homeomorphism between \(X\) and \(\phi(X)\) and \(\phi(X)\) is an open, dense subset of \(K\). Thus a compactification is a way of nicely embedding the space \(X\) into a compact space \(K\).

For example if \(X\) is the real line \(\mathbb{R}\), then the circle \(S^1\) and the stereographic projection is a compactification of \(X\). In this case the image of \(X\) is all of the circle apart from one point. Since the circle is compact, this is indeed a compactification. This is an example of a one-point compactification. An idea which we will return to later.

Comparing Compactifications

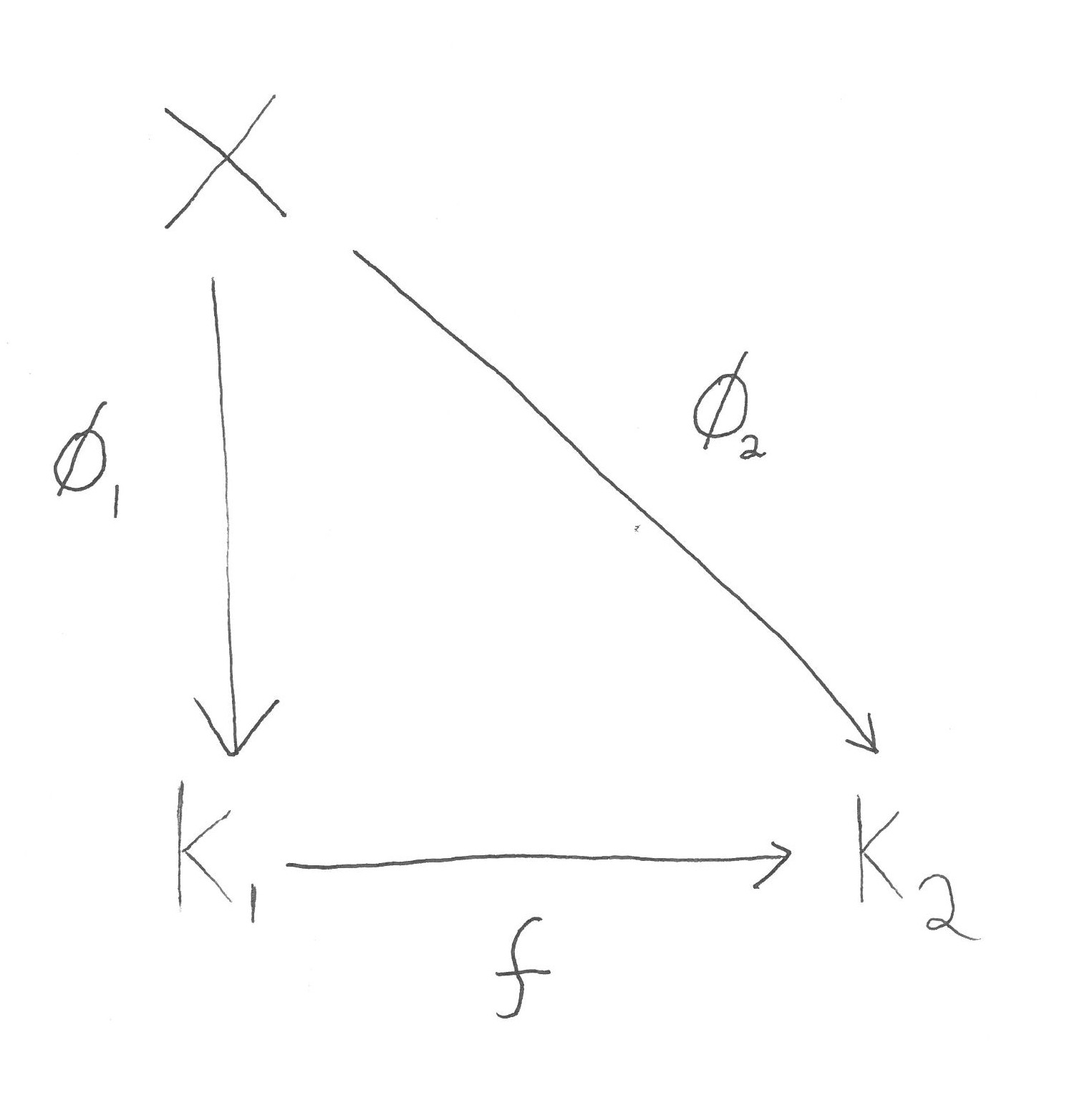

A space \(X\) will in general have many compactifications and we would like to compare these different compactifications. Suppose that \((K_1,\phi_1)\) and \((K_2, \phi_2)\) are two compactifications. Then a morphism from \((K_1,\phi_1)\) to \((K_2,\phi_2)\) is a continuous map \(f : K_1 \rightarrow K_2\) such that \(\phi_2 = f \circ \phi_1\). That is, the below diagram commutes:

Hence we have a morphism from \((K_1,\phi_1)\) to \((K_2,\phi_2)\) precisely when the embedding \(\phi_2 : X \rightarrow K_2\) extends to a map \(f : K_1 \rightarrow K_2\). Since \(\phi_1(X)\) is dense in \(K_1\), if such a function \(f\) exists, it is unique.

Note that the map \(f \) must be surjective since \(\phi_2(X)\) is dense in \(K_2\) and \(g(K_1)\) is a closed set containing \(\phi_2(X)\). We can think of the compactification \((K_1,\phi_1)\) as being “bigger” or “more general” than the compactification \((K_2, \phi_2)\) as \(f\) is a surjection onto \(K_2\). More formally we will say that \((K_1,\phi_1)\) is finer than \((K_2, \phi _2)\) and equivalently that \((K_2, \phi _2)\) is coarser than \((K_1, \phi _1)\) whenever there is a morphism from \((K_1, \phi_1)\) to \((K_2,\phi_2)\). Note that the composition of two morphism of compactifications is again a morphism of compactifications. Thus we can talk about the category of compactifications of a space. The compactifications \((K_1, \phi _1)\) and \((K_2, \phi _2)\) are isomorphic if there exists a morphism \(g\) between \((K_1, \phi _1)\) and \((K_2, \phi _2)\) such that \(g\) is a homeomorphism between \(K_1\) and \(K_2\).

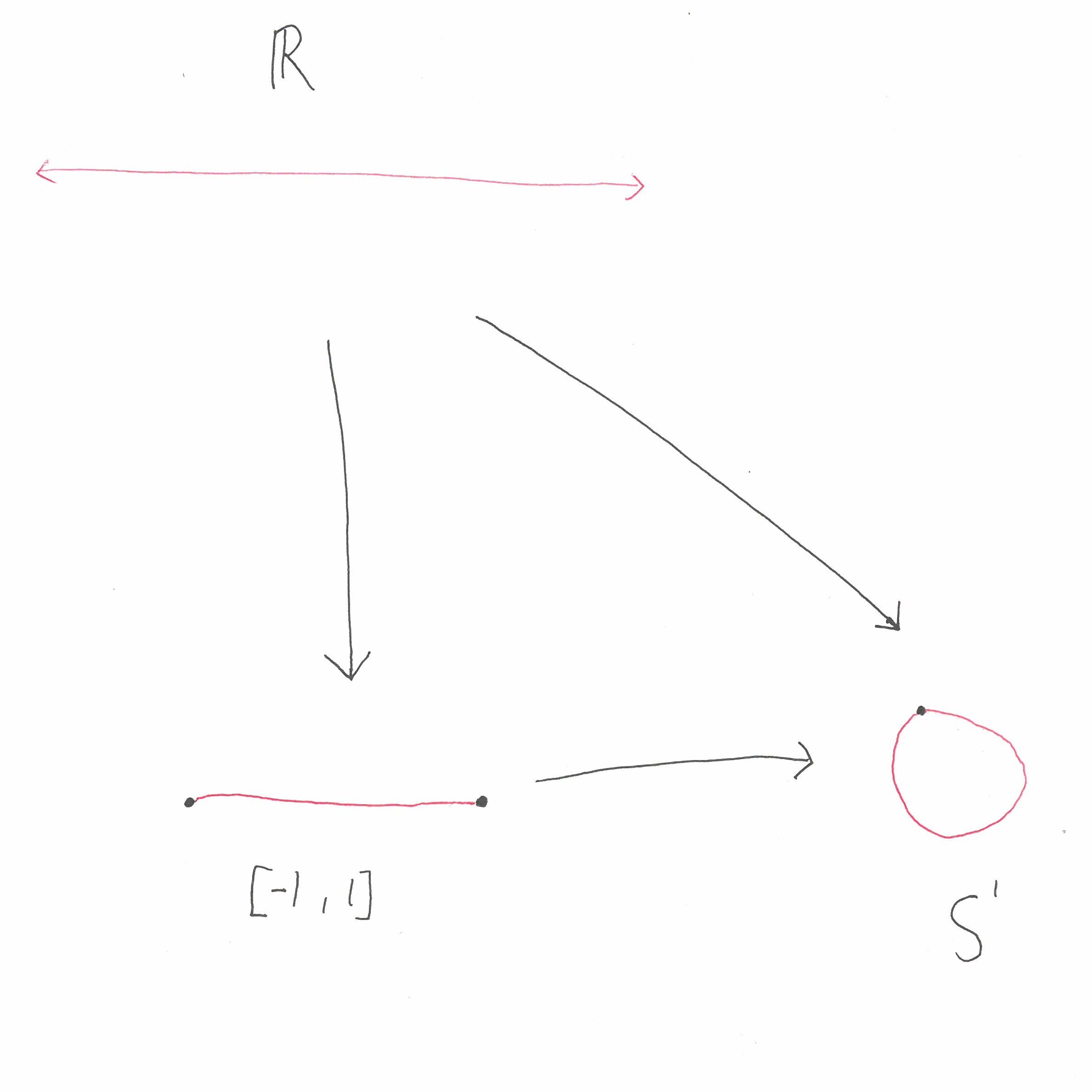

For example again let \(X = \mathbb{R}\). Then the closed interval \([-1,1]\) is again a compactification of \(\mathbb{R}\) with the map \((x,y) \mapsto \frac{x}{1+|x|}\) which maps \(\mathbb{R}\) onto the open interval \((-1,1)\). We can then create a morphism from \([-1,1]\) to the circle by sending the endpoints of \([-1,1]\) to the top of the circle and sending the interior of \([-1,1]\) to the rest of the circle. We can perform this map in such a way that the following diagram commutes:

Thus we have a morphism from the compactification \([-1,1]\) to the compactification \(S^1\). Thus the compactification \([-1,1]\) is finer than the compactification \(S^1\).

Now that we have a way of comparing compactifications of \(X\) we can ask about the existence of extremal compactifications of \(X\). Does there exists a compactification of \(X\) that is the coarser than any other compactification? Or one which is finer than any other? From a category-theory perspective, we are interested in the existence of terminal and initial objects in the category of compactifications of \(X\). We will first show the existence of a coarsest or “least general” compactification.

The one point compactification

A coarsest compactification would be a terminal object in the category of compactifications. That is a compactification \((\alpha X, i)\) with the property that for all compactification \((K, \phi)\) there is a unique extension \(g : K \rightarrow \alpha X\) of \(i : X \rightarrow \alpha X\). If such a coarsest compactification exists, then it is unique up to isomorphism. Thus we can safely refer to the coarsest compactification.

The one point compactification of \(X\) is constructed by adding a single point denoted by \(\infty\) to \(X\). It is defined to be the set \(\alpha X = X \sqcup \{ \infty\}\) with the topology given by the collection of open sets in \(X\) and sets of the form \(\alpha X \setminus K\) for \(K \subseteq X\) a compact subset. The map \(i : X \rightarrow \alpha X\) is given by simply including \(X\) into \(\alpha X = X \sqcup \{\infty\}\).

The one point compactification is the coarsest compactification of \(X\). Let \((K,\phi)\) be another compactification of \(X\). Then the map \(g : K \rightarrow \alpha X\) given by

\(g(y) = \begin{cases} i(\phi^{-1}(y)) & \text{if } y \in \phi(X),\\ \infty & \text{if } y \notin \phi(X), \end{cases}\)

is the unique morphism from \((K,f)\) to \((\alpha X, i)\).

The Stone-Čech compactification

A Stone-Čech compactification of \(X\) is a compactification \((\beta X,j)\) which is the finest compactification of \(X\). That is \((\beta X,j)\) is an initial object in the category of a compactifications of \(X\) and so for every compactification \((K,f)\) there exists a unique morphism from \((\beta X,j)\) to \((K,f)\). Thus any embedding \(f : X \rightarrow K\), has a unique extension \(g : \beta X \rightarrow K\). As with coarest compactification of \(X\), the Stone-Čech compactification of \(X\) is unique up to isomorphism and thus we will talk of the Stone-Čech compactification.

Unlike the one point compactification of \(X\), there is no simple description of \(\beta X\) even when \(X\) is a very simple space such as \(\mathbb{N}\) or \(\mathbb{R}\). To show the existence of a Stone-Čech compactification of any space \(X\) we will need to make a detour and develop some tools from the study of C*-algebras which will be the topic of the next blog post.

2 thoughts on “The Stone-Čech Compactification – Part 1”