The auxiliary variables sampler is a general Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) technique for sampling from probability distributions with unknown normalizing constants [1, Section 3.1]. Specifically, suppose we have \(n\) functions \(f_i : \mathcal{X} \to (0,\infty)\) and we want to sample from the probability distribution \(P(x) \propto \prod_{i=1}^n f_i(x).\) That is

\(\displaystyle{ P(x) = \frac{1}{Z}\prod_{i=1}^n f_i(x)},\)

where \(Z = \sum_{x \in \mathcal{X}} \prod_{i=1}^n f_i(x)\) is a normalizing constant. If the set \(\mathcal{X}\) is very large, then it may be difficult to compute \(Z\) or sample from \(P(x)\). To approximately sample from \(P(x)\) we can run an ergodic Markov chain with \(P(x)\) as a stationary distribution. Adding auxiliary variables is one way to create such a Markov chain. For each \(i \in \{1,\ldots,n\}\), we add a auxiliary variable \(U_i \ge 0\) such that

\(\displaystyle{P(U \mid X) = \prod_{i=1}^n \mathrm{Unif}[0,f_i(X)]}.\)

That is, conditional on \(X\), the auxiliary variables \(U_1,\ldots,U_n\) are independent and \(U_i\) is uniformly distributed on the interval \([0,f_i(X)]\). If \(X\) is distributed according to \(P\) and \(U_1,\ldots,U_n\) have the above auxiliary variable distribution, then

\(\displaystyle{P(X,U) =P(X)P(U\mid X)\propto \prod_{i=1}^n f_i(X) \frac{1}{f_i(X)} I[U_i \le f(X_i)] = \prod_{i=1}^n I[U_i \le f(X_i)]}.\)

This means that the joint distribution of \((X,U)\) is uniform on the set

\(\widetilde{\mathcal{X}} = \{(x,u) \in \mathcal{X} \times (0,\infty)^n : u_i \le f(x_i) \text{ for all } i\}.\)

Put another way, suppose we could jointly sample \((X,U)\) from the uniform distribution on \(\widetilde{\mathcal{X}}\). Then, the above calculation shows that if we discard \(U\) and only keep \(X\), then \(X\) will be sampled from our target distribution \(P\).

The auxiliary variables sampler approximately samples from the uniform distribution on \(\widetilde{\mathcal{X}}\) is by using a Gibbs sampler. The Gibbs samplers alternates between sampling \(U’\) from \(P(U \mid X)\) and then sampling \(X’\) from \(P(X \mid U’)\). Since the joint distribution of \((X,U)\) is uniform on \(\widetilde{\mathcal{X}}\), the conditional distributions \(P(X \mid U)\) and \(P(U \mid X)\) are also uniform. The auxiliary variables sampler thus transitions from \(X\) to \(X’\) according to the two step process

- Independently sample \(U_i\) uniformly from \([0,f_i(X)]\).

- Sample \(X’\) uniformly from the set \(\{x \in \mathcal{X} : f_i(x) \ge u_i \text{ for all } i\}\).

Since the auxiliary variables sampler is based on a Gibbs sampler, we know that the joint distribution of \((X,U)\) will converge to the uniform distribution on \(\mathcal{X}\). So when we discard \(U\), the distribution of \(X\) will converge to the target distribution \(P\)!

Auxiliary variables in practice

To perform step 2 of the auxiliary variables sampler we have to be able to sample uniformly from the sets

\(\mathcal{X}_u = \{x \in \mathcal{X}:f_i(x) \ge u_i \text{ for all } i\}. \)

Depending on the nature of the set \(\mathcal{X}\) and the functions \(f_i\), it might be difficult to do this. Fortunately, there are some notable examples where this step has been worked out. The very first example of auxiliary variables is the Swendsen-Wang algorithm for sampling from the Ising model [2]. In this model it is possible to sample uniformly from \(\mathcal{X}_u\). Another setting where we can sample exactly is when \(\mathcal{X}\) is the real numbers \(\mathcal{R}\) and each \(f_i\) is an increasing function of \(x\). This is explored in [3] where they apply auxiliary variables to sampling from Bayesian posteriors.

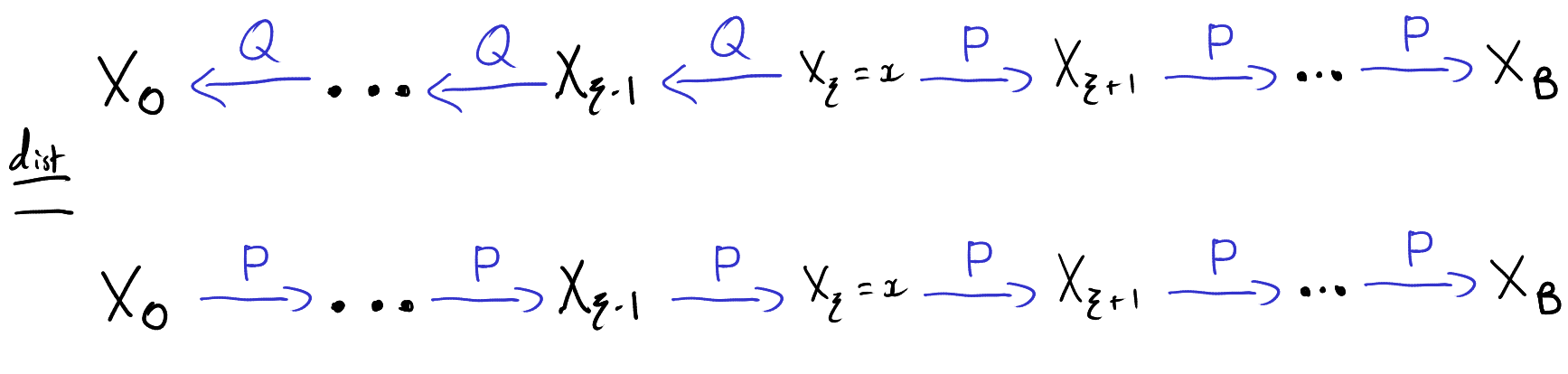

There is an alternative to sampling exactly from the uniform distribution on \(\mathcal{X}_u\). Instead of sampling \(X’\) uniformly from \(\mathcal{X}_u\), we can run a Markov chain from the old \(X\) that has the uniform distribution as a stationary distribution. This approach leads to another special case of auxiliary variables which is called “slice sampling” [4].

References

[1] Andersen HC, Diaconis P. Hit and run as a unifying device. Journal de la societe francaise de statistique & revue de statistique appliquee. 2007;148(4):5-28. http://www.numdam.org/item/JSFS_2007__148_4_5_0/

[2] Swendsen RH, Wang JS. Nonuniversal critical dynamics in Monte Carlo simulations. Physical review letters. 1987 Jan 12;58(2):86. https://journals.aps.org/prl/abstract/10.1103/PhysRevLett.58.86

[3] Damlen P, Wakefield J, Walker S. Gibbs sampling for Bayesian non‐conjugate and hierarchical models by using auxiliary variables. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B (Statistical Methodology). 1999 Apr;61(2):331-44. https://rss.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/1467-9868.00179

[4] Neal RM. Slice sampling. The annals of statistics. 2003 Jun;31(3):705-67. https://projecteuclid.org/journals/annals-of-statistics/volume-31/issue-3/Slice-sampling/10.1214/aos/1056562461.full