The ratio of uniforms distribution is a useful distribution for rejection sampling. It gives a simple and fast way to sample from discrete distributions like the hypergeometric distribution1. To use the ratio of uniforms distribution in rejection sampling, we need to know the distributions density. This post summarizes some properties of the ratio of uniforms distribution and computes its density.

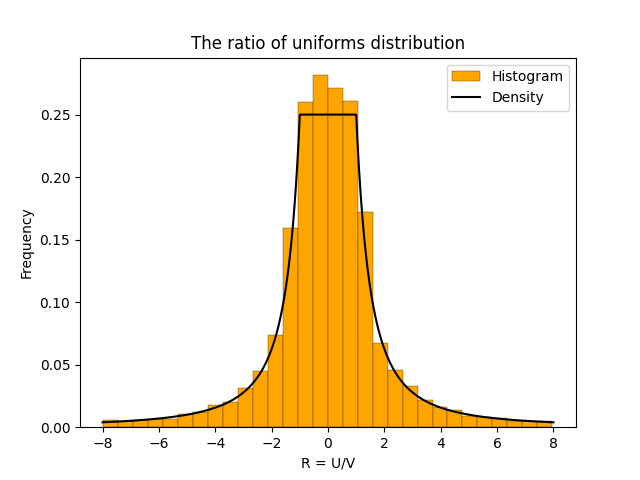

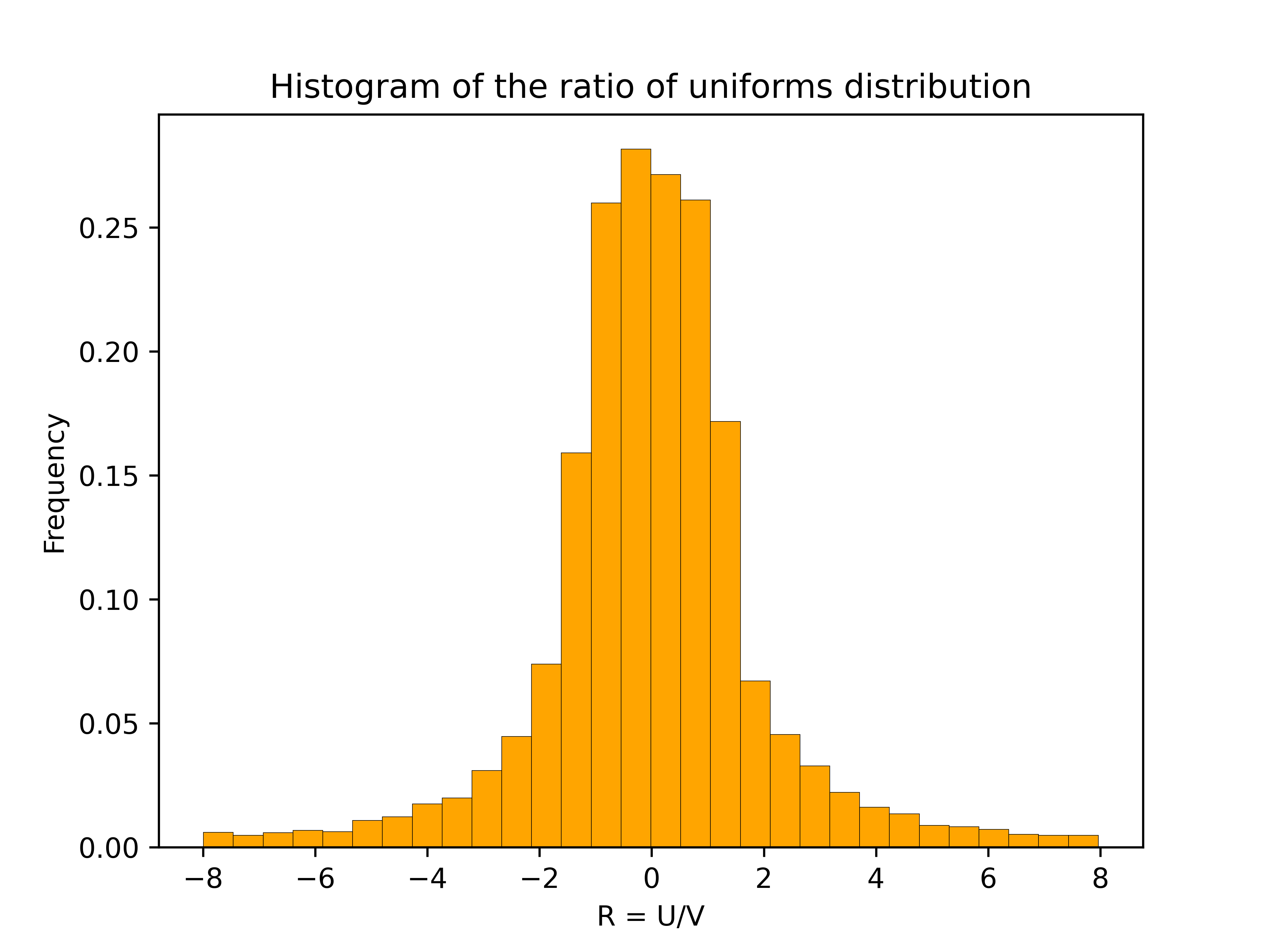

The ratio of uniforms distribution is the distribution of the ratio of two independent uniform random variables. Specifically, suppose \(U \in [-1,1]\) and \(V \in [0,1]\) are independent and uniformly distributed. Then \(R = U/V\) has the ratio of uniforms distribution. The plot below shows a histogram based on 10,000 samples from the ratio of uniforms distribution2.

The histogram has a flat section in the middle and then curves down on either side. This distinctive shape is called a “table mountain”. The density of \(R\) also has a table mountain shape.

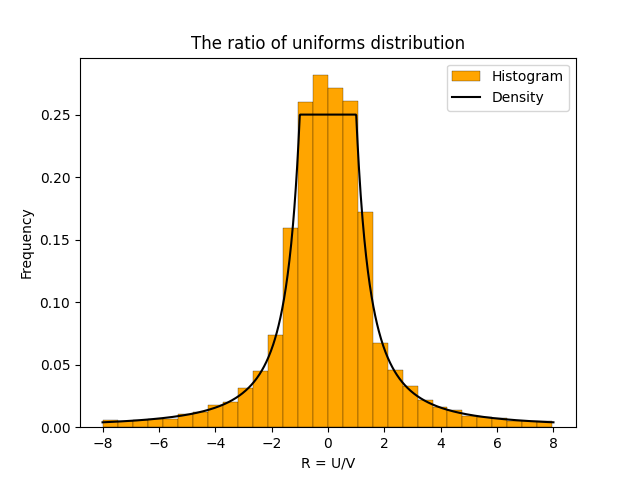

And here is the density plotted on top of the histogram.

A formula for the density of \(R\) is

\[h(R) = \begin{cases} \frac{1}{4} & \text{if } -1 \le R \le 1, \\\frac{1}{4R^2} & \text{if } R < -1 \text{ or } R > 1.\end{cases}\]

The first case in the definition of \(h\) corresponds to the flat part of the table mountain. The second case corresponds to the sloping curves. The rest of this post use geometry to derive the above formula for \(h(R)\).

Calculating the density

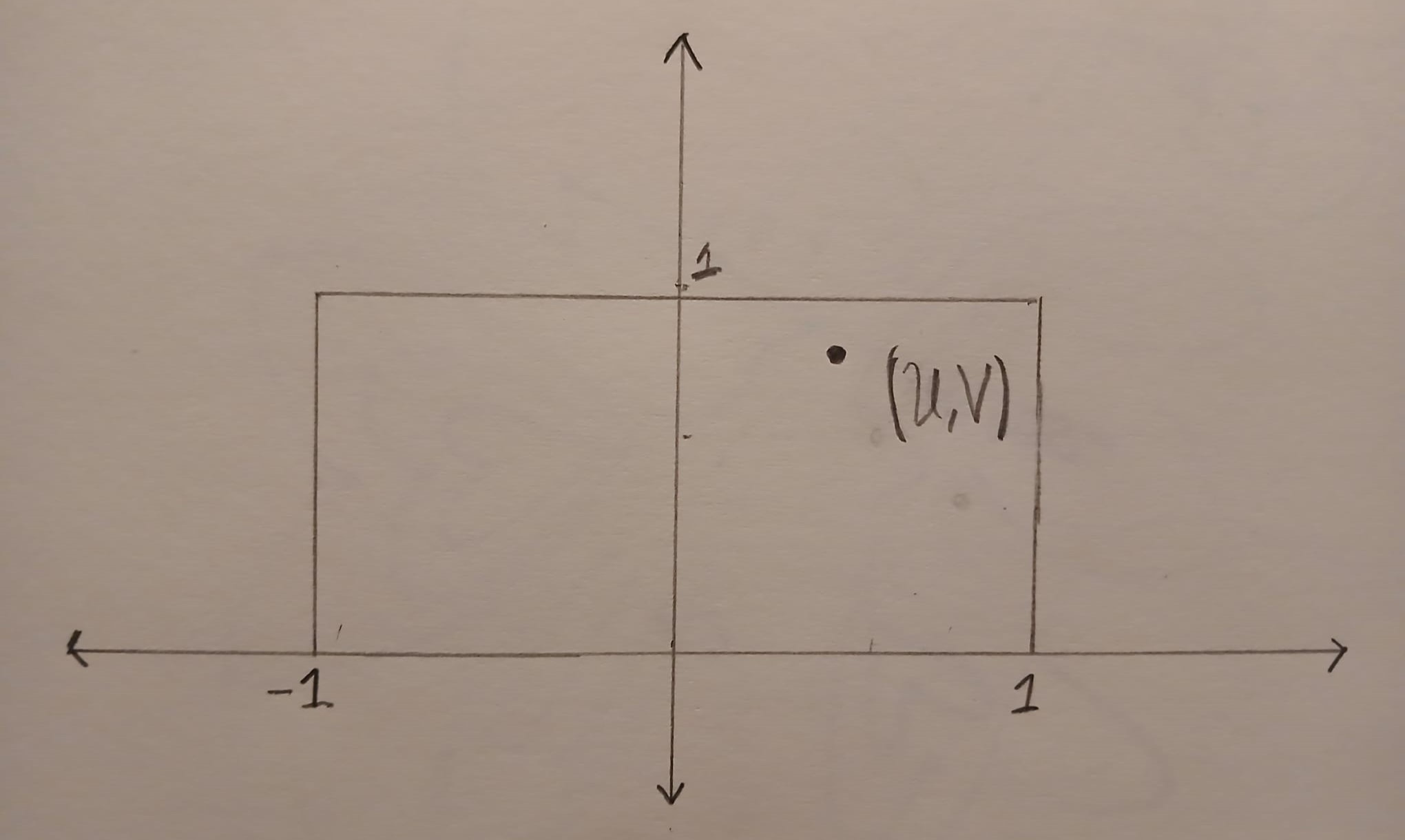

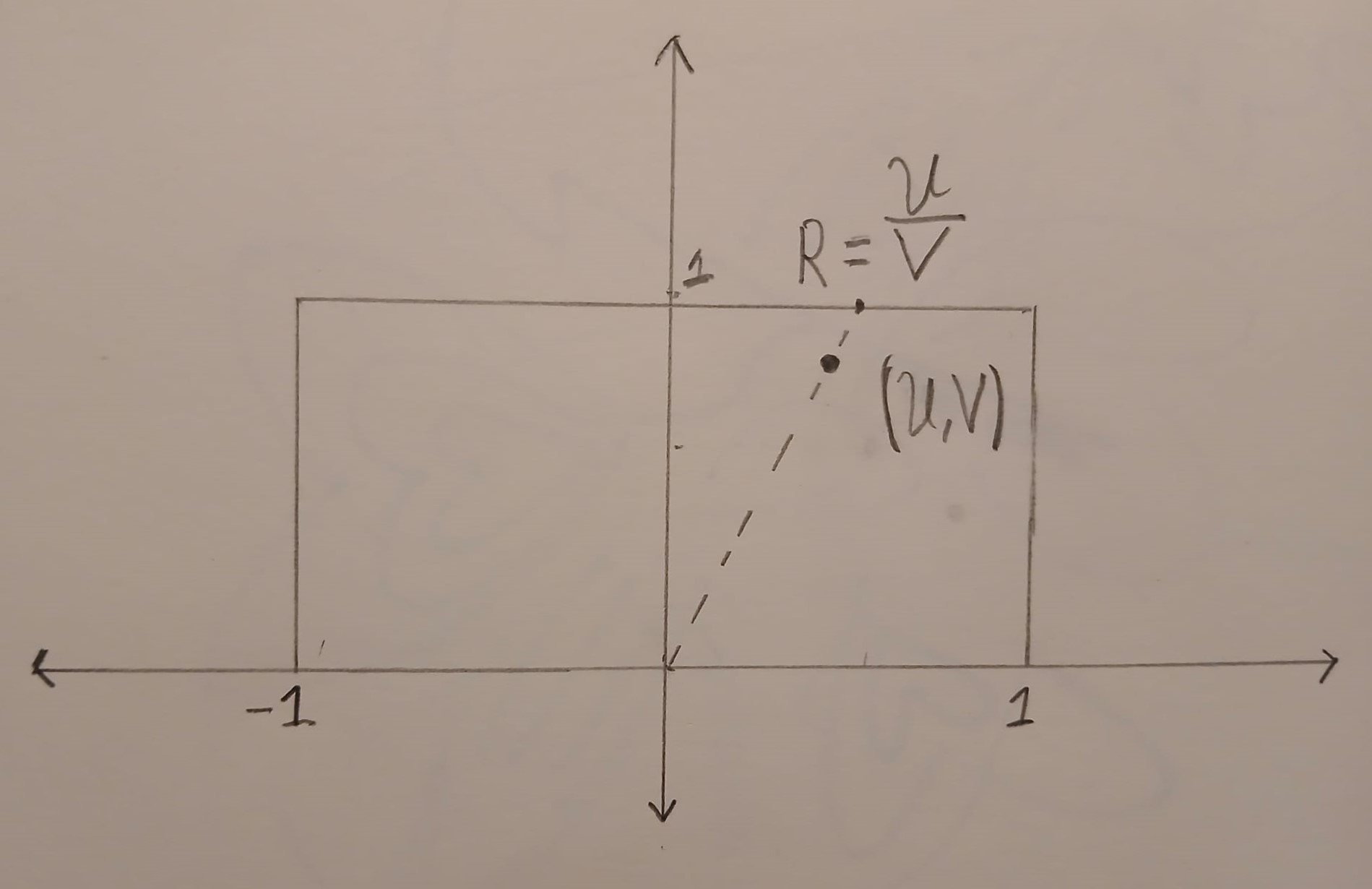

The point \((U,V)\) is uniformly distributed in the box \(B=[-1,1] \times [0,1]\). The image below shows an example of a point \((U,V)\) inside the box \(B\).

We can compute the ratio \(R = U/V\) geometrically. First we draw a straight line that starts at \((0,0)\) and goes through \((U,V)\). This line will hit the horizontal line \(y=1\). The \(x\) coordinate at this point is exactly \(R=U/V\).

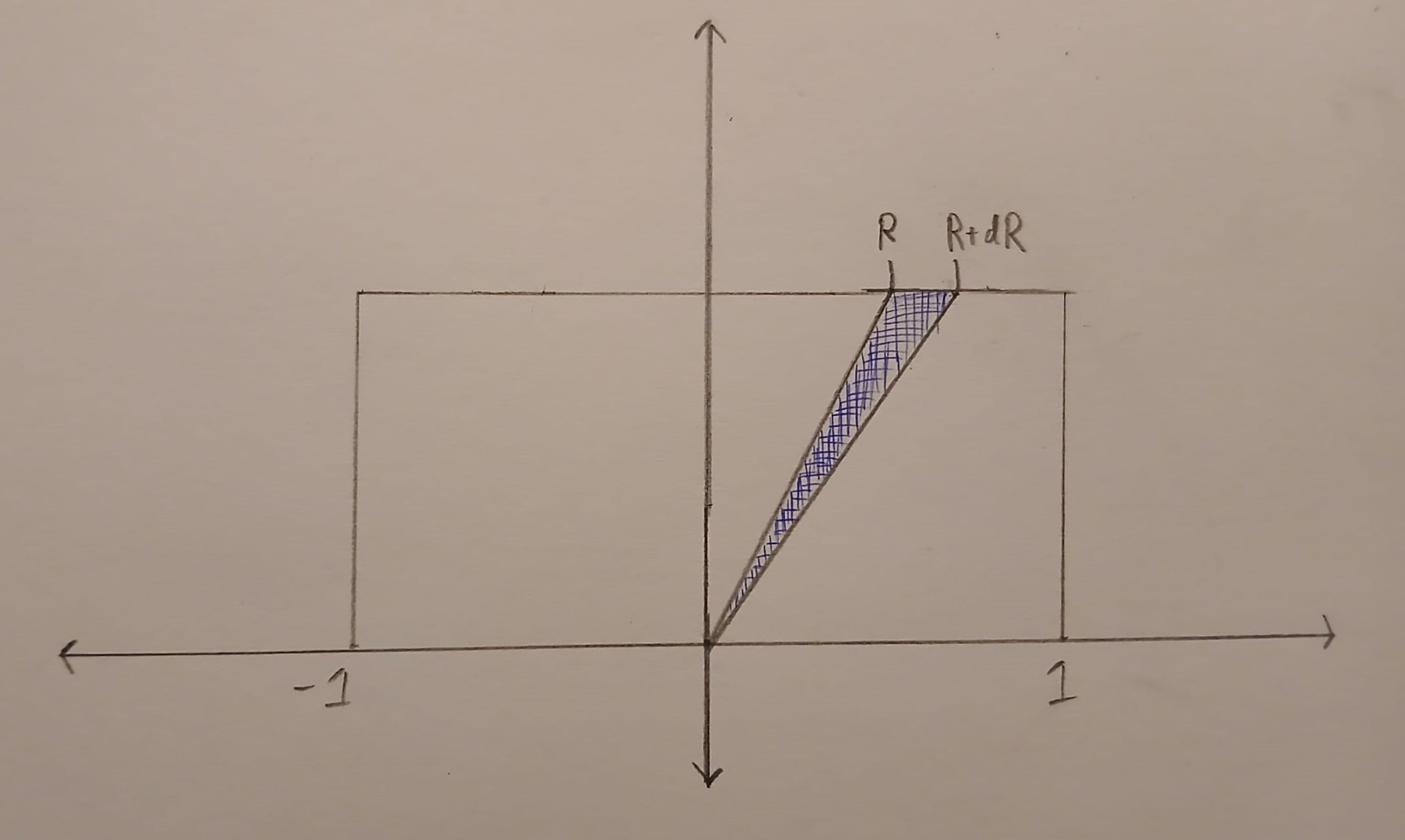

In the above picture, all of the points on the dashed line map to the same value of \(R\). We can compute the density of \(R\) by computing an area. The probability that \(R\) is in a small interval \([R,R+dR]\) is \(\frac{\text{Area}(\{(u,v) \in B : u/v \in [R, R+dR]\})}{\text{Area}(B)}\) which is equal to

\[\frac{1}{2}\text{Area}(\{(u,v) \in B : u/v \in [R, R+dR]\}).\]

If we can compute the above area, then we will know the density of \(R\) because by definition

\(\displaystyle{h(R) = \lim_{dR \to 0} \frac{1}{2dR}\text{Area}(\{(u,v) \in B : u/v \in [R, R+dR]\})}.\)

We will first work on the case when \(R\) is between \(-1\) and \(1\). In this case, the set \(\{(u,v) \in B : u/v \in [R, R+dR]\}\) is a triangle. This triangle is drawn in blue below.

The horizontal edge of this triangle has length \(dR\). The perpendicular height of the triangle from the horizontal edge is \(1\). This means that

\[\text{Area}(\{(u,v) \in B : u/v \in [R, R+dR]\}) =\frac{dR}{2}.\]

And so, when \(R \in [-1,1]\) we have

\(\displaystyle{h(R) = \lim_{dR\to 0} \frac{1}{2dR}\times \frac{dR}{2}=\frac{1}{4}}.\)

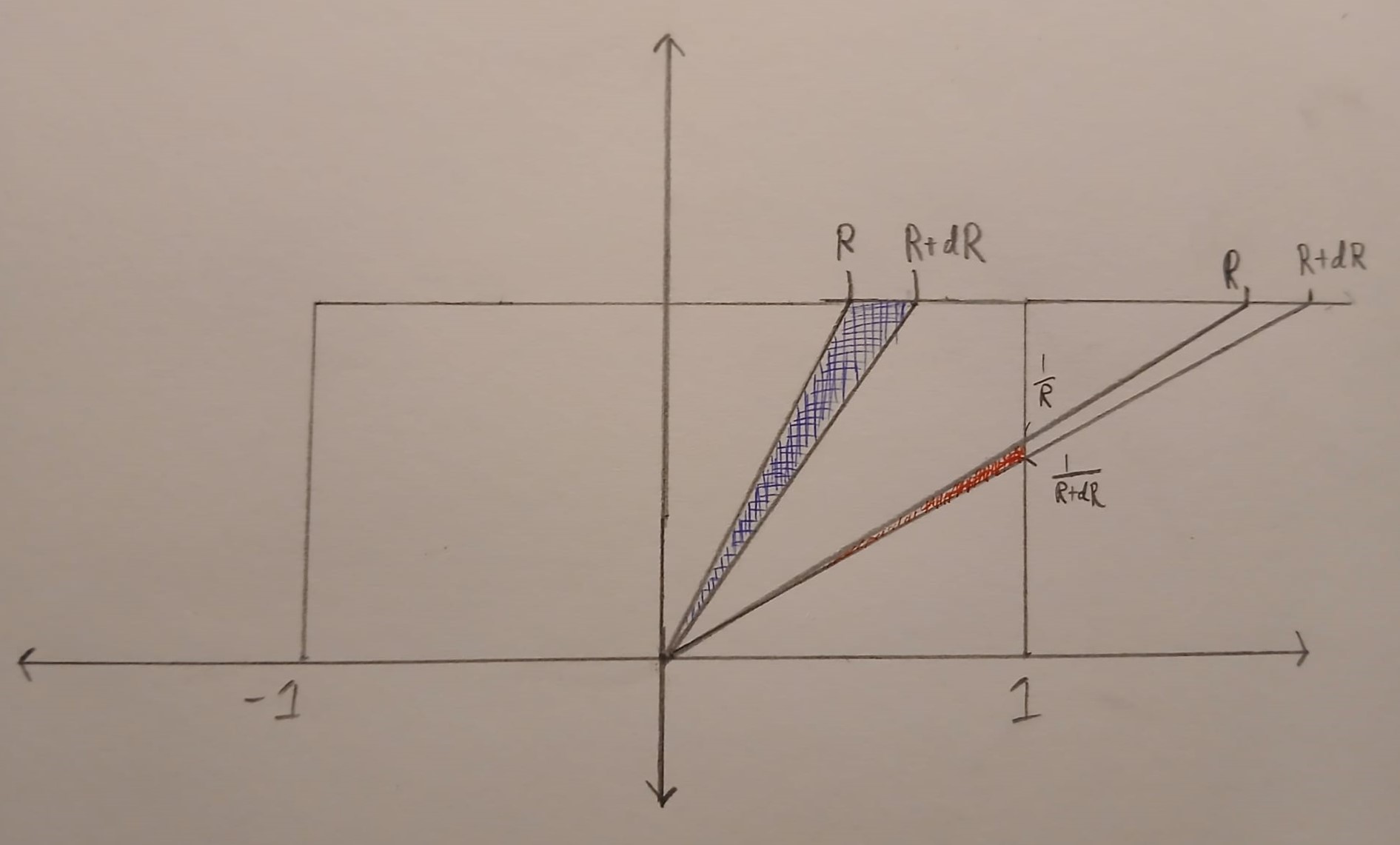

Now let’s work on the case when \(R\) is bigger than \(1\) or less than \(-1\). In this case, the set \(\{(u,v) \in B : u/v \in [R, R+dR]\}\) is again triangle. But now the triangle has a vertical edge and is much skinnier. Below the triangle is drawn in red. Note that only points inside the box \(B\) are coloured in.

The vertical edge of the triangle has length \(\frac{1}{R} – \frac{1}{R+dR}= \frac{dR}{R(R+dR)}\). The perpendicular height of the triangle from the vertical edge is \(1\). Putting this together

\(\displaystyle{\text{Area}(\{(u,v) \in B : u/v \in [R, R+dR]\}) =\frac{dR}{2R(R+dR)}}.\)

And so

\(\displaystyle{h(R) = \lim_{dR \to 0} \frac{1}{2dR} \times \frac{dR}{2 R(R+dR)} = \frac{1}{4R^2}}.\)

And so putting everything together

\(\displaystyle{h(R) = \begin{cases} \frac{1}{4} & \text{if } -1 \le R \le 1, \\\frac{1}{4R^2} & \text{if } R < -1 \text{ or } R > 1.\end{cases}}\)

Footnotes and references

- https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/718718 ↩︎

- For visual purposes, I restricted the sample to values of \(R\) between \(-8\) and \(8\). This is because the ratio of uniform distribution has heavy tails. This meant that there were some very large values of \(R\) that made the plot hard to see. ↩︎