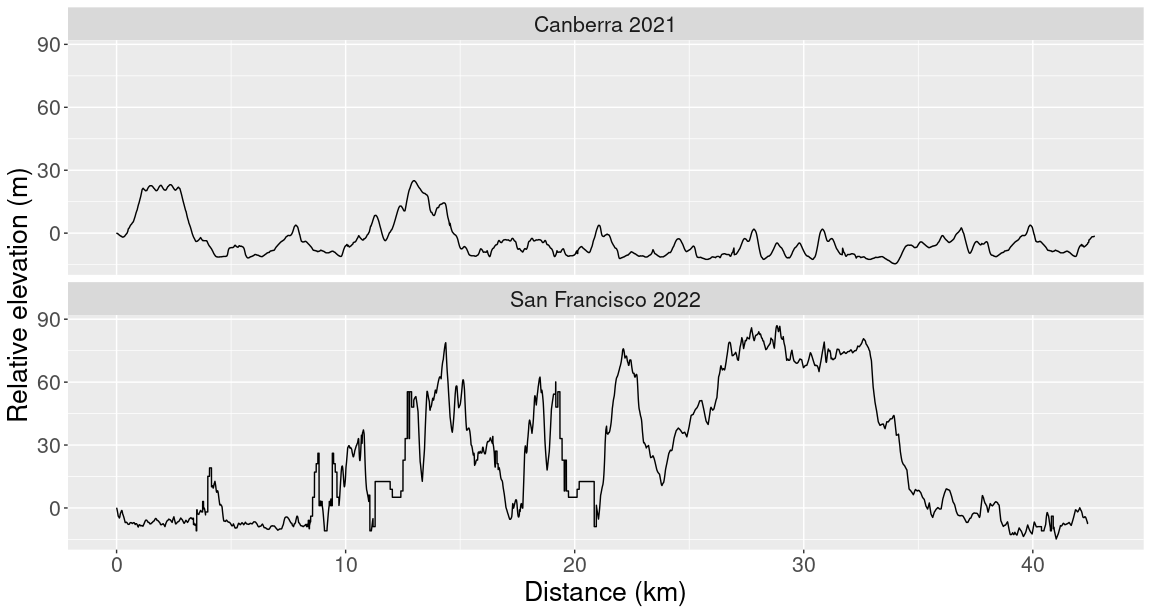

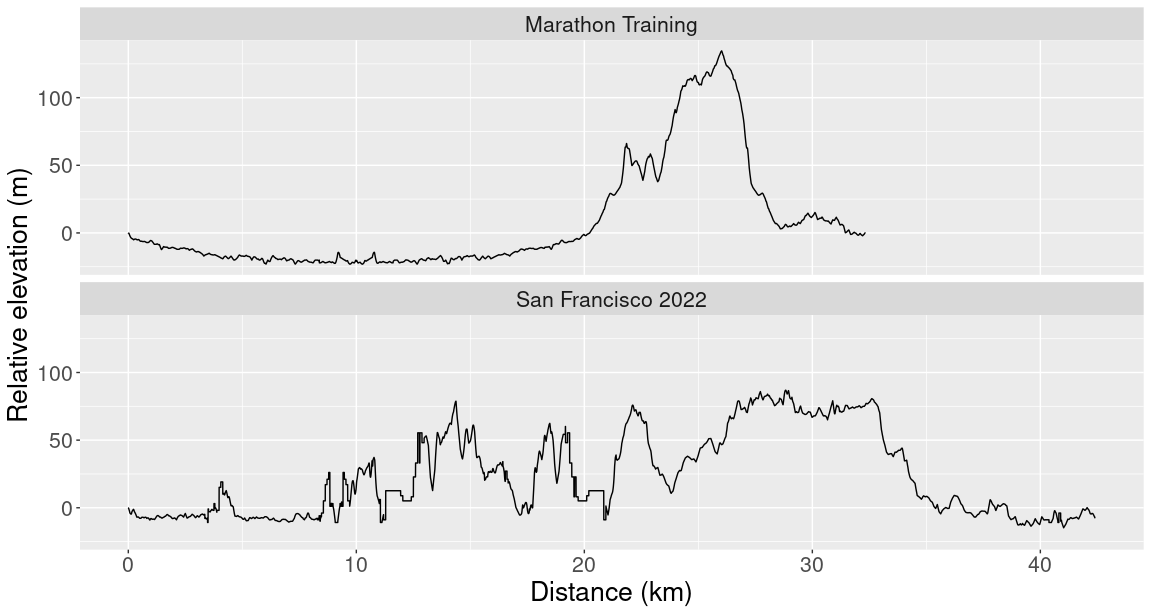

Total variation is a way of measuring how much a function \(f:[a,b] \to \mathbb{R}\) “wiggles”. In this post, I want to motivate the definition of total variation by talking about elevation in marathon running.

Comparing marathon courses

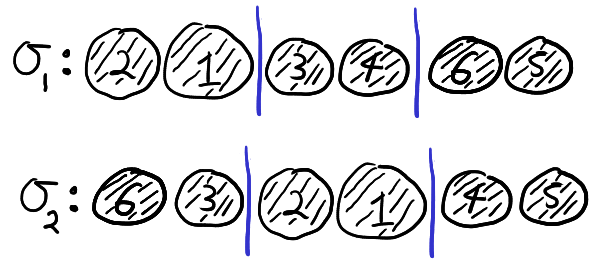

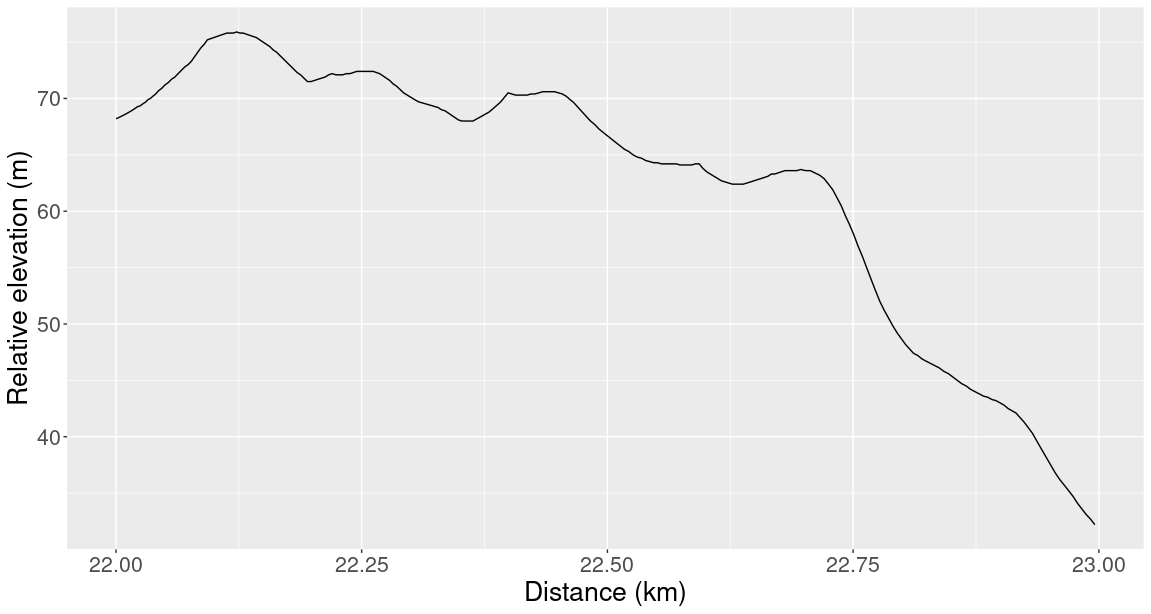

On July 24th I ran the 2022 San Francisco (SF) marathon. All marathons are the same distance, 42.2 kilometres (26.2 miles) but individual courses can vary greatly. Some marathons are on road and others are on trails. Some locations can be hot and others can be rainy. And some, such as the SF marathon, can be much hillier than others. Below is a plot comparing the elevation of the Canberra marathon I ran last year to the elevation of the SF marathon:

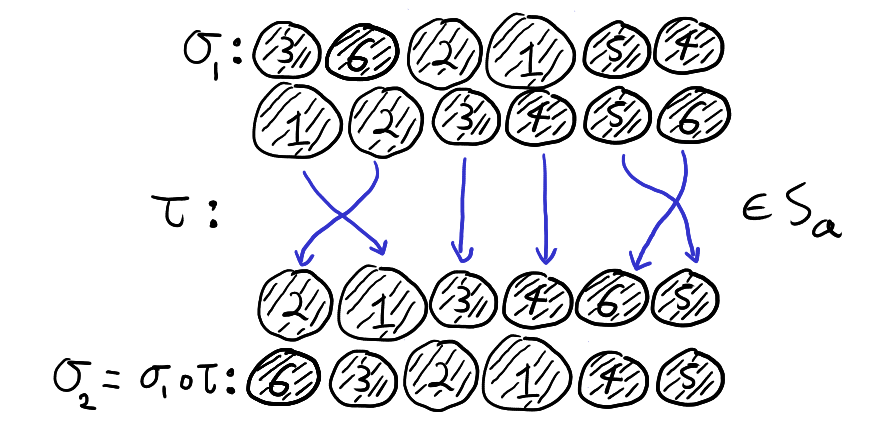

Immediately, you can see that the range of elevation during the San Francisco marathon was much higher than the range of elevation during the Canberra marathon. However, what made the SF marathon hard wasn’t any individual incline but rather the sheer number of ups and downs. For comparison, the plot below shows elevation during a 32 km training run and elevation during the SF marathon:

You can see that my training run was mostly flat but had one big hill in the last 10 kilometres. The maximum relative elevation on my training run was about 50 meters higher than the maximum relative elevation of the marathon, but overall the training run graph is a lot less wiggly. This meant there were far more individual hills during the marathon and so the first 32 km of the marathon felt a lot tougher than the training run. By comparing these two runs, you can see that the elevation range can hide important information about the difficulty of a run. We also need to pay attention to how wiggly the elevation curve is.

Wiggliness Scores

So far our definition of wiggliness has been imprecise and has relied on looking at a graph of the elevation. This makes it hard to compare two runs and quickly decide which one is wigglier. It would be convenient if there was a “wiggliness score” – a single number we could assign to each run which measured the wiggliness of the run’s elevation. Bellow we’ll see that total variation does exactly this.

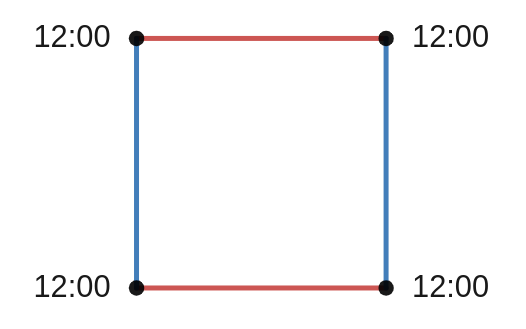

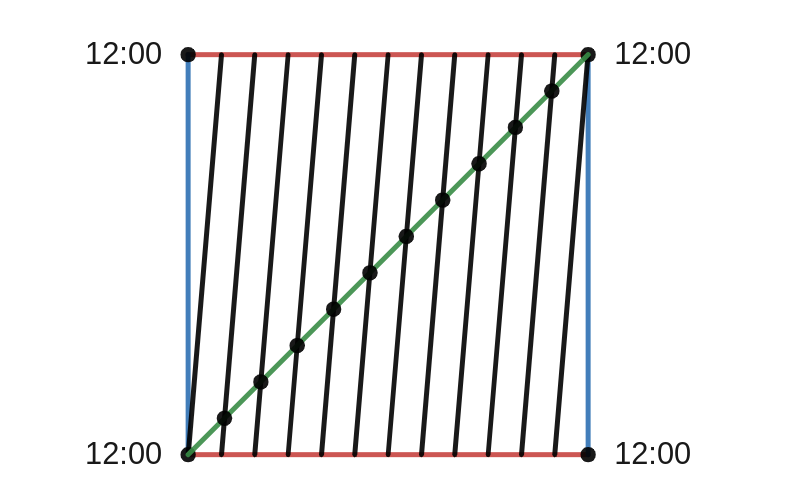

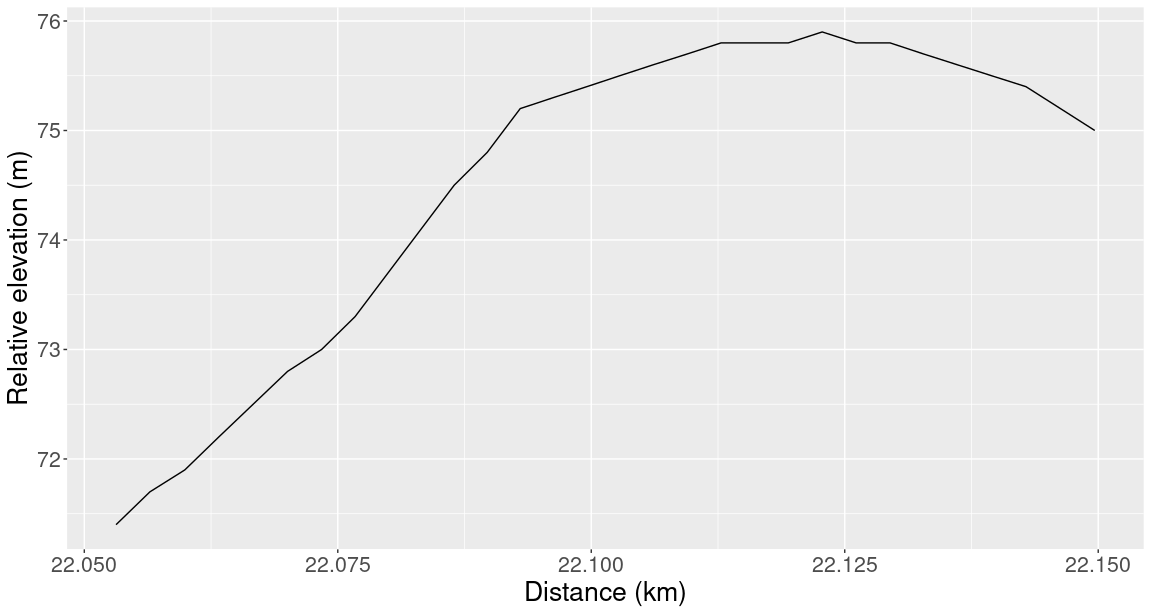

If we zoom in on one of the graphs above, we would see that it actually consists of tiny straight line segments. For example, let’s look at the 22nd kilometre of the SF marathon. In this plot it looks like elevation is a smooth function of distance:

But if we zoom in on a 100 m stretch, then we see that the graph is actually a series of straight lines glued together:

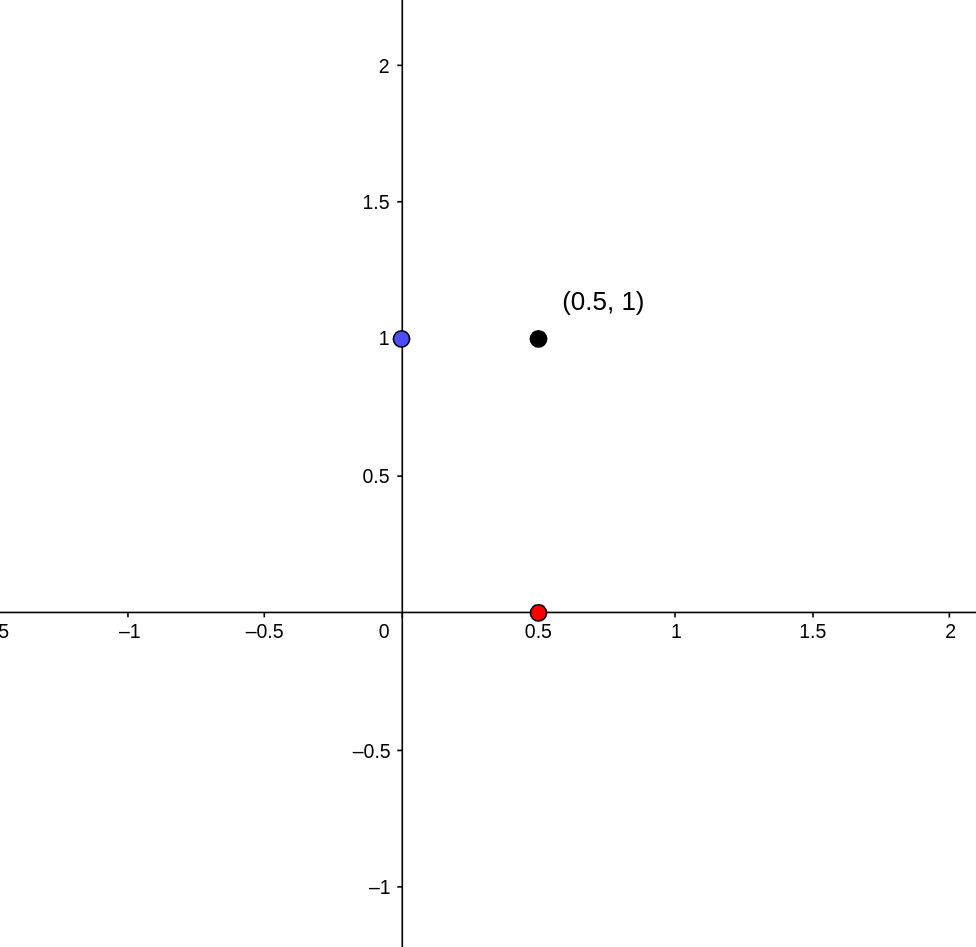

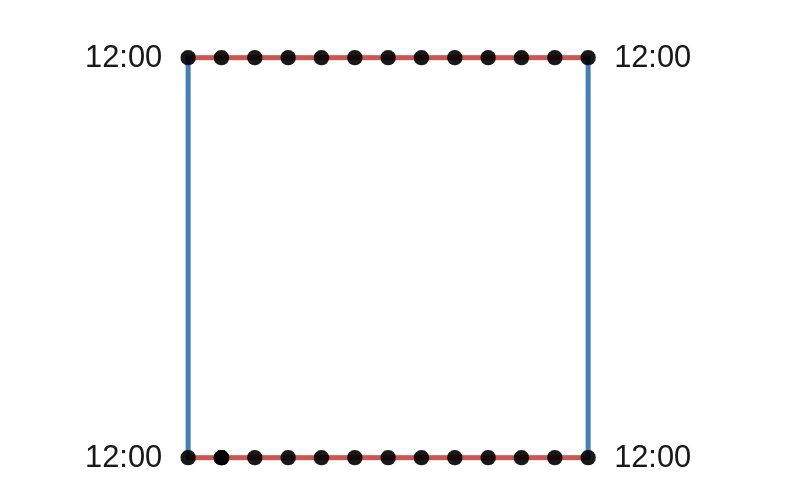

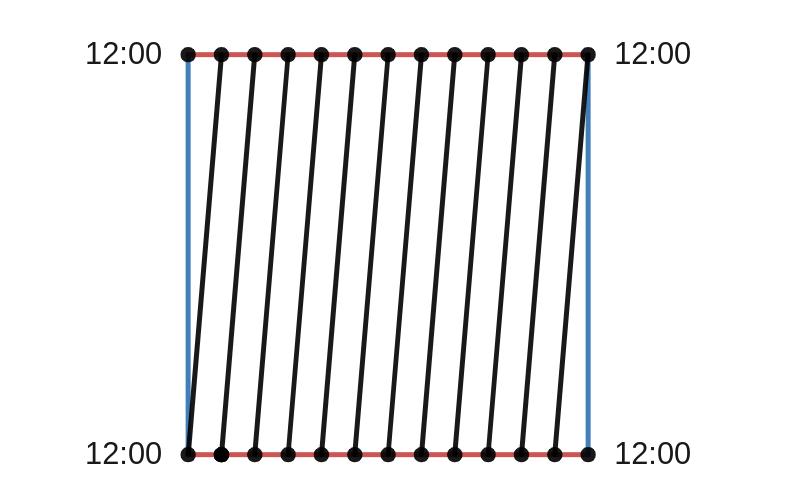

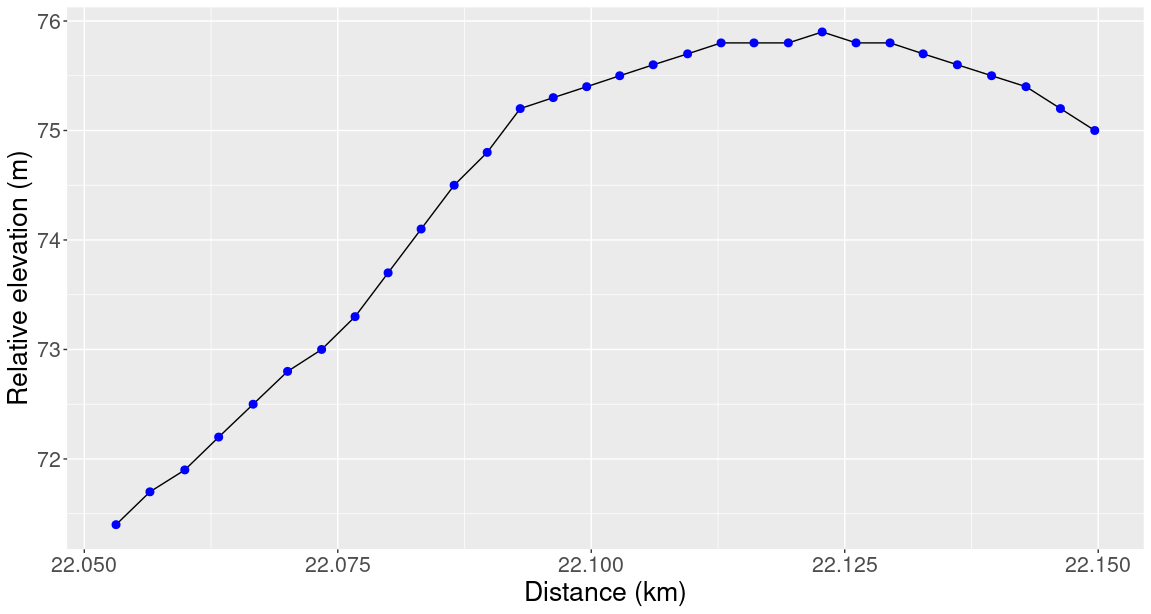

This is because these graphs are made using my GPS watch which makes one recording per second. If we place dots at each of these times, then the straight lines become clearer:

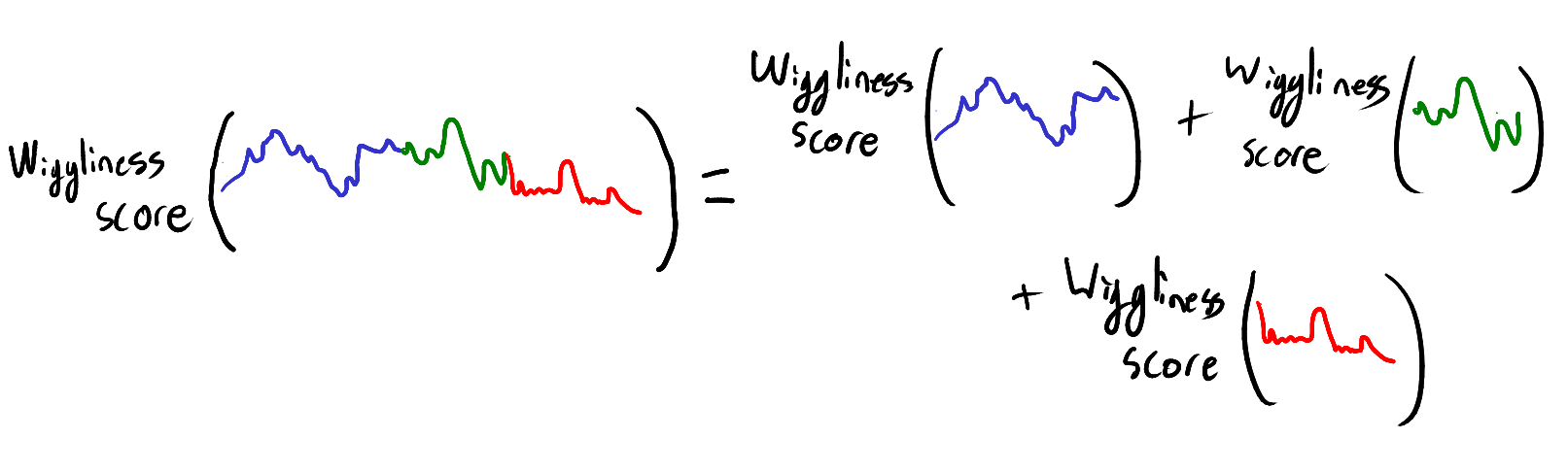

We can use these blue dots to define the graph’s wiggliness score. The wiggliness score should capture how much the graph varies across its domain. This suggests that wiggliness scores should be additive. By additive, I mean that if we split the domain into a finite number of pieces, then the wiggliness score across the whole domain should be the sum of the wiggliness score of each segment.

In particular, the wiggliness score for the SF marathon is equal to the sum of the wiggliness score of each section between two consecutive blue dots. This means we only need to quantify how much the graph varies between consecutive blue dots. Fortunately, between two such dots, the graph is a straight line. The amount that a straight line varies is simply the distance between the y-value at the start and the y-value at the end. Thus, by adding up all these little distances we can get a wiggliness score for the whole graph. This wiggliness score is used in mathematics, where it is called the total variation.

Here are the wiggliness scores for the three runs shown above:

| Run | Wiggliness score |

| Canberra Marathon 2021 | 617 m |

| Training run | 742 m |

| SF Marathon 2022 | 2140 m |

Total Variation

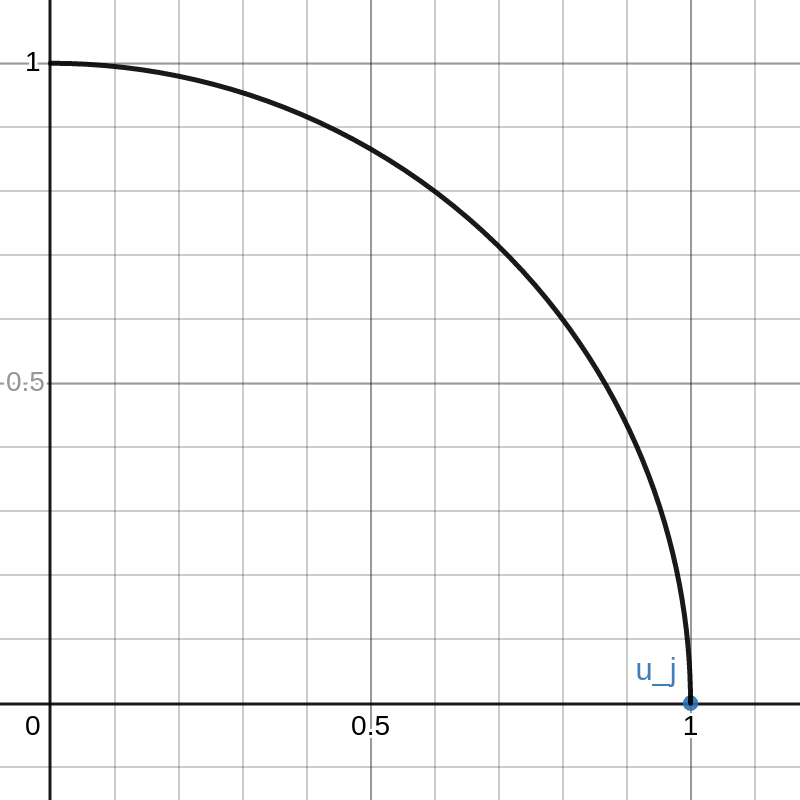

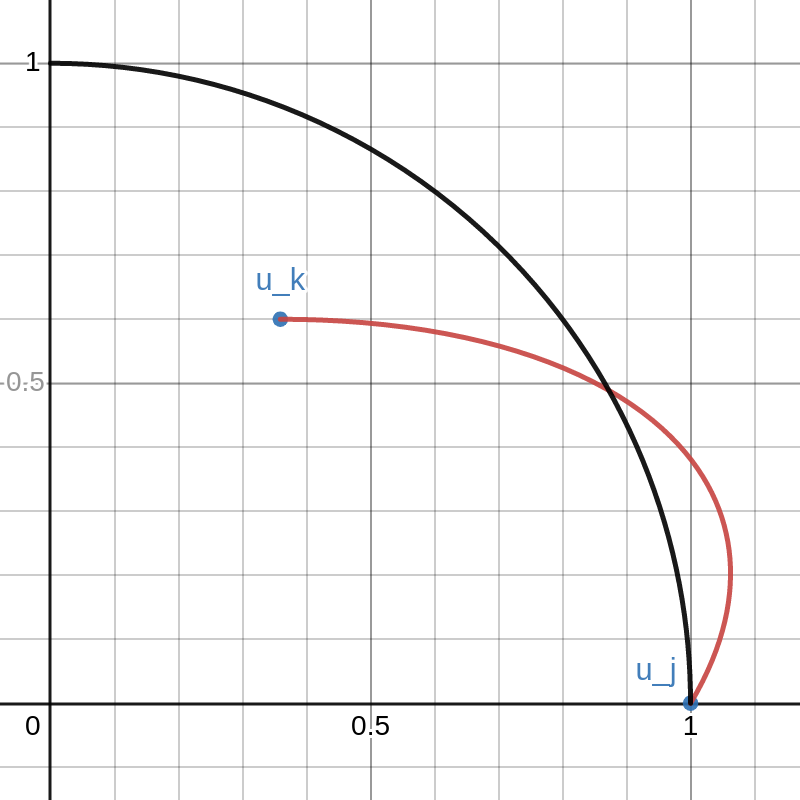

We’ve seen that by breaking up a run into little pieces, we can calculate the total variation over the course of the run. But how can we calculate the total variation of an arbitrary function \(f:[a,b] \to \mathbb{R}\)?

Our previous approach won’t work because the function \(f\) might not be made up of straight lines. But we can approximate \(f\) with other functions that are made of straight lines. We can calculate the total variation of these approximations using the approach we used for the marathon runs. Then we define the total variation of \(f\) as the limit of the total variation of each of these approximations.

To make this precise, we will work with partitions of \([a,b]\). A partition of \([a,b]\) is a finite set of points \(P = \{x_0, x_1,\ldots,x_n\}\) such that:

\(a = x_0 < x_1 < \ldots < x_n = b\).

That is, \(x_0, x_1,\ldots,x_n\) is a collection of increasing points in \([a,b]\) that start at \(a\) and end at \(b\). For a given partition \(P\) of \([a,b]\), we calculate how much the function \(f\) varies over the points in the partition \(P\). As with the blue dots above, we can simply add up the distance between consecutive \(y\) values \(f(x_i)\) and \(f(x_{i-1})\). In symbols, we define \(V_P(f)\) (the variation over \(f\) over the partition \(P\)) to be:

\(V_P(f) = \sum\limits_{i=1}^n |f(x_i)-f(x_{i-1})|\).

To define the variation of \(f\) over the interval \([a,b]\), we can imagine taking finer and finer partitions of \([a,b]\). To do this, note that whenever we add more points to a partition, the total variation over that partition can only increase. Thus, we can think of the total variation of \(f\) as the maximum total variation over any partition. We denote the total variation of \(f\) by \(V(f)\) and define it as:

\(V(f) = \sup\{V_P(f) : P \text{ is a partition of } [a,b]\}\).

Surprisingly, there exist continuous function for which the total variation is infinite. Sample paths of the Brownian motion are canonical examples of continuous functions with infinite total variation. Such functions would be very challenging runs.

Some Limitations

Total variation does a good job of measuring how wiggly a function is but it has some limitations when applied to course elevation. The biggest issue is that total variation treats inclines and declines symmetrically. A steep line sloping down increases the total variation by the same amount as a line with the same slope going upwards. This obviously isn’t true when running; an uphill is very different to a downhill.

To quantify how much a function wiggles upwards, we could use the same ideas but replace the absolute value \(|f(x_i)-f(x_{i-1})|\) with the positive part \((f(x_i)-f(x_{i-1}))_+ = \max\{f(x_i)-f(x_{i-1}),0\}\). This means that only the lines that slope upwards will count towards the wiggliness score. Lines that slope downwards get a wiggliness score of zero.

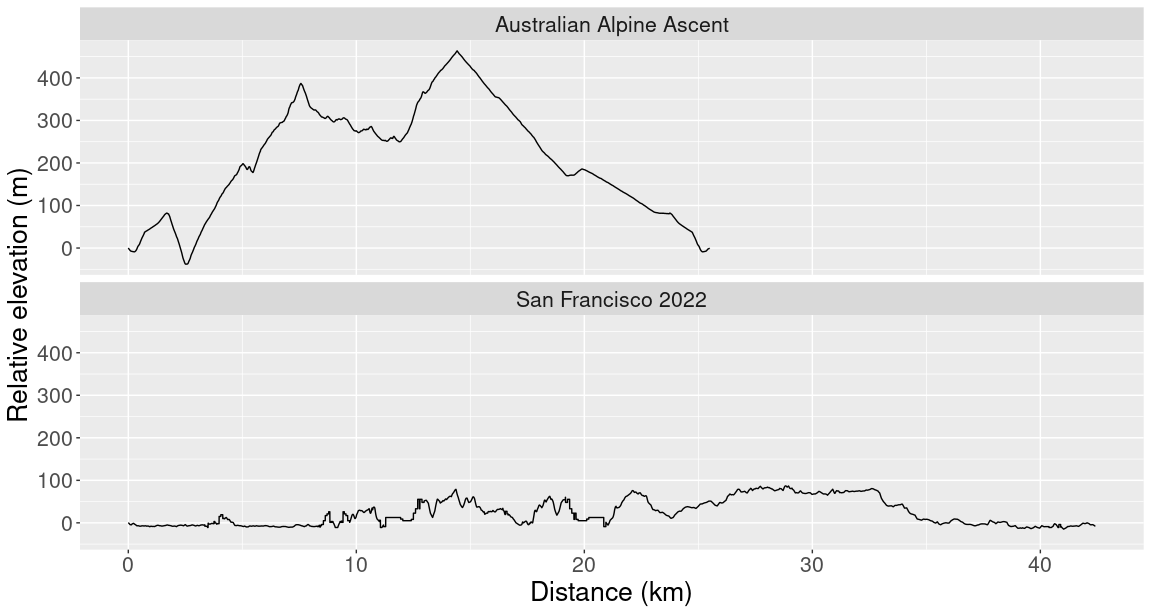

Another limitation of total variation is that it measures total wiggliness across the whole domain rather than average wiggliness. This isn’t much of a problem when comparing runs of a similar length, but when comparing runs of different lengths, total variation can give surprising results. Below is a comparison between the Australian Alpine Ascent and the SF marathon:

The Australian Alpine Ascent is a 25 km run that goes up Australia’s tallest mountain. Despite the huge climbs during the Australian Alpine Ascent, the SF marathon has a higher total variation. Since the Australian Alpine Ascent was shorter, it gets a lower wiggliness score (1674 m vs 2140 m). For this comparison it would be better to divide each wiggliness score by the runs’ distance.

Summary

Despite these limitations, I still think that total variation is a useful metric for comparing two runs. It doesn’t tell you exactly how tough a run will be but if you already know the run’s distance and starting/finishing elevation, then the total variation helps you know what to expect.