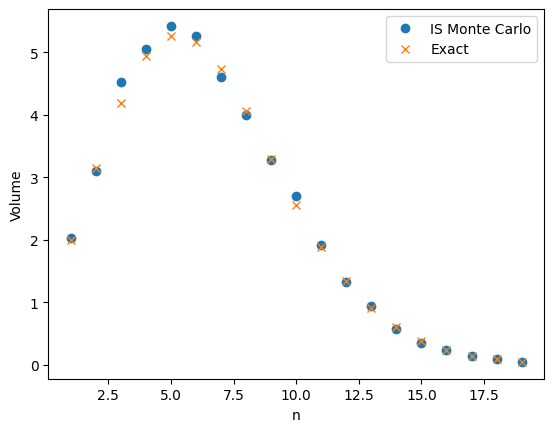

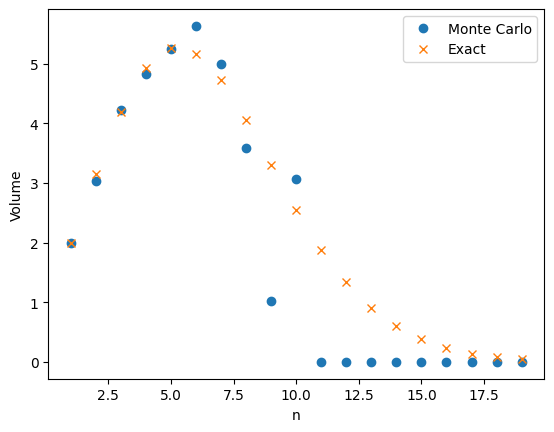

My last post was about using importance sampling to estimate the volume of high-dimensional ball. The two figures below compare plain Monte Carlo to using importance sampling with a Gaussian proposal. Both plots use \(M=1,000\) samples to estimate \(v_n\), the volume of an \(n\)-dimensional ball

A friend of mine pointed out that the relative error does not seem to increase with the dimension \(n\). He thought it was too good to be true. It turns out he was right and the relative error does increase with dimension but it increases very slowly. To estimate \(v_n\) the number of samples needs to grow on the order of \(\sqrt{n}\).

To prove this, we will use the paper The sample size required for importance sampling by Chatterjee and Diaconis [1]. This paper shows that the sample size for importance sampling is determined by the Kullback-Liebler divergence. The relevant result from their paper is Theorem 1.3. This theorem is about the relative error in using importance sampling to estimate a probability.

In our setting the proposal distribution is \(Q=\mathcal{N}(0,\frac{1}{n}I_n)\). That is the distribution \(Q\) is an \(n\)-dimensional Gaussian vector with mean \(0\) and covariance \(\frac{1}{n}I_n\). The conditional target distribution is \(P\) the uniform distribution on the \(n\) dimensional ball. Theorem 1.3 in [1] tells us how many samples are needed to estimate \(v_n\). Informally, the required sample size is \(M = O(\exp(D(P \Vert Q)))\). Here \(D(P\Vert Q)\) is the Kullback-Liebler divergence between \(P\) and \(Q\).

To use this theorem we need to compute \(D(P \Vert Q)\). Kullback-Liebler divergence is defined as integral. Specifically

\(\displaystyle{D(P\Vert Q) = \int_{\mathbb{R}^n} \log\frac{P(x)}{Q(x)}P(x)dx}\)

Computing the high-dimensional integral above looks challenging. Fortunately, it can reduced to a one-dimensional integral. This is because both the distributions \(P\) and \(Q\) are rotationally symmetric. To use this, define \(P_r,Q_r\) to be the distribution of the norm squared under \(P\) and \(Q\). That is if \(X \sim P\), then \(\Vert X \Vert_2^2 \sim P_R\) and likewise for \(Q_R\). By the rotational symmetry of \(P\) and \(Q\) we have

\(D(P\Vert Q) = D(P_R \Vert Q_R).\)

We can work out both \(P_R\) and \(Q_R\). The distribution \(P\) is the uniform distribution on the \(n\)-dimensional ball. And so for \(X \sim P\) and any \(r \in [0,1]\)

\(\mathbb{P}(\Vert X \Vert_2^2 \le r) = \frac{v_n r^n}{v_n} = r^n.\)

Which implies that \(P_R\) has density \(P_R(r)=nr^{n-1}\). This means that \(P_R\) is a Beta distribution with parameters \(\alpha = n, \beta = 1\). The distribution \(Q\) is a multivariate Gaussian distribution with mean \(0\) and variance \(\frac{1}{n}I_n\). This means that if \(X \sim Q\), then \(\Vert X \Vert_2^2 = \sum_{i=1}^n X_i^2\) is a scaled chi-squared variable. The shape parameter of \(Q_R\) is \(n\) and scale parameter is \(1/n\). The density for \(Q_R\) is therefor

\(Q_R(r) = \frac{n^{n/2}}{2^{n/2}\Gamma(n/2)}r^{n/2-1}e^{-nx/2}\)

The Kullback-Leibler divergence between \(P\) and \(Q\) is therefor

\(\displaystyle{D(P\Vert Q)=D(P_R\Vert Q_R) = \int_0^1 \log \frac{P_R(r)}{Q_R(r)} P_R(r)dr}\)

Getting Mathematica to do the above integral gives

\(D(P \Vert Q) = -\frac{1+2n}{2+2n} + \frac{n}{2}\log(2 e) – (1-\frac{n}{2})\log n + \log \Gamma(\frac{n}{2}).\)

Using the approximation \(\log \Gamma(z) \approx (z-\frac{1}{2})\log(z)-z+O(1)\) we get that for large \(n\)

\(D(P \Vert Q) = \frac{1}{2}\log n + O(1)\).

And so the required number of samples is \(O(\exp(D(P \Vert Q)) = O(\sqrt{n}).\)

[1] Chatterjee, Sourav, and Persi Diaconis. “The sample size required in importance sampling.” The Annals of Applied Probability 28, no. 2 (2018): 1099–1135. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26542331. (Public preprint here https://arxiv.org/abs/1511.01437)