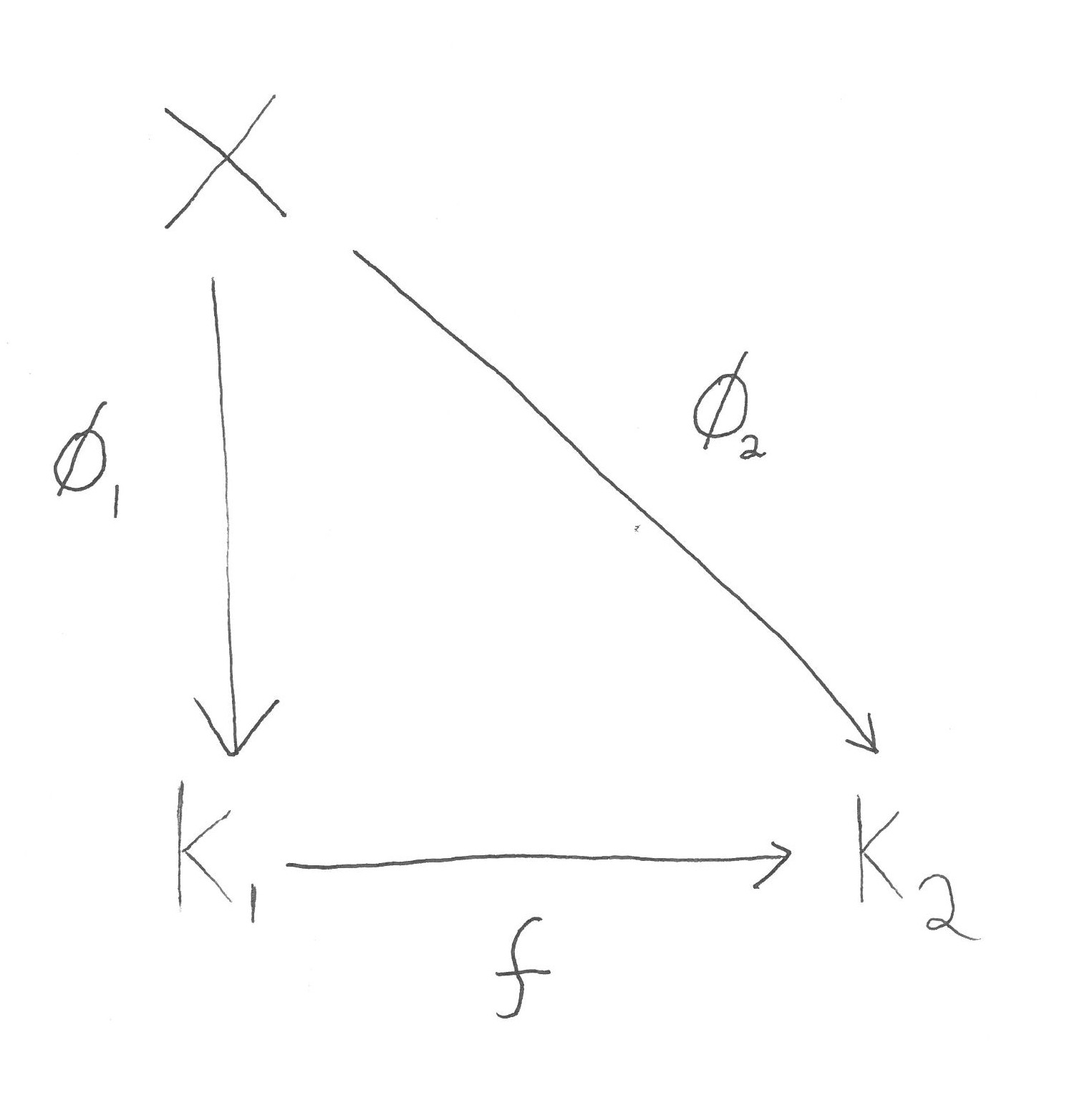

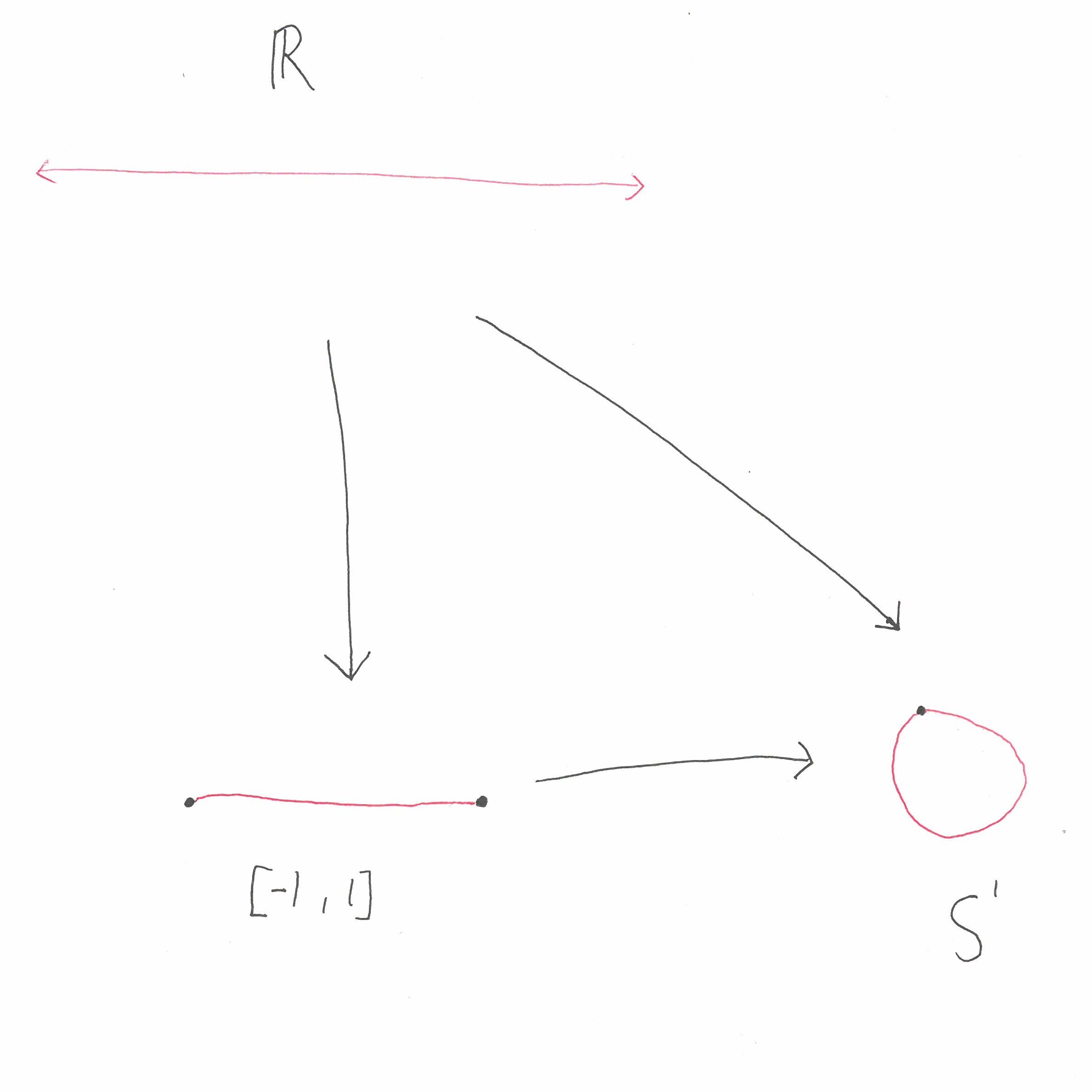

In the first blog post of this series we discussed two compactifications of \(\mathbb{R}\). We had the circle \(S^1\) and the interval \([-1,1]\). In the second post of this series we saw that there is a correspondence between compactifications of \(\mathbb{R}\) and sub algebras of \(C_b(\mathbb{R})\). In this blog post we will use this correspondence to uncover another compactification of \(\mathbb{R}\).

Since \(S^1\) is the one point compactification of \(\mathbb{R}\) we know that it corresponds to the subalgebra \(C_\infty(\mathbb{R})\). This can be seen by noting that a continuous function on \(S^1\) is equivalent to a continuous function, \(f\), on \(\mathbb{R}\) such that \(\lim_{x \to +\infty} f(x)\) and \(\lim_{x \to -\infty} f(x)\) both exist and are equal. On the other hand the compactification \([-1,1]\) corresponds to the space of functions \(f \in C_b(\mathbb{R})\) such that \(\lim_{x \to +\infty} f(x)\) and \(\lim_{x \to – \infty}f(x)\) both exist (but these limits need not be equal).

We can also play this game in reverse. We can start with an algebra \(A \subseteq C_b(\mathbb{R})\) and ask what compactification of \(\mathbb{R}\) it corresponds to. For example we may take \(A\) to be the following sub algebra

\(\{g+h \mid g,h \in C(\mathbb{R}), g(x+2\pi)=g(x) \text{ for all } x \in \mathbb{R} \text{ and } \lim_{x \to \pm \infty} h(x)=0 \}.\)

That is \(A\) contains precisely those functions in \(C_b(\mathbb{R})\) that are the perturbation of a \(2\pi\) periodic function by a function that vanishes at both \( \infty\) and \(– \infty\). Since any constant function is \(2 \pi\) periodic, we know that \(C_\infty(\mathbb{R})\) is contained in \(A\). Thus, as explained in the previous blog post, we know that \(\sigma(A)\) corresponds to a compactification of \(\mathbb{R}\).

Recall that \(\sigma(A)\) consists of all the non-zero continuous C*-homeomorphisms from \(A\) to \(\mathbb{C}\). The space \(\sigma(A)\) contains a copy o \(\mathbb{R}\) as a subspace. A point \(t \in \mathbb{R}\) corresponds to the homeomorphism \(\omega_t\) given by \(\omega_t(f)=f(t)\). There are also a circle’s worth of homeomorphisms \(\nu_p\) given by \(\nu_p(f) = \lim_{k \to \infty} f(2 \pi k+p)\) for \(p \in [0,2\pi)\). The homeomorphism \(\nu_p\) isolates the value of the \(2\pi\) periodic part of \(f\) at the point \(p\). This is because if \(f = g+h\) with \(g\) a \(2 \pi\) periodic function and \(h\) a function that vanishes at infinity. Then

\(\nu_p(f) = \lim\limits_{k \to \infty} (g(2 \pi k + p)+h(2 \pi k + p)) = g(p)+\lim\limits_{k \to \infty} h(2 \pi k + p) = g(p)\).

Thus we know that the topological space \(\sigma(A)\) is the union of a line and a circle. We now just need to work out the topology of how these to spaces are put together to make \(\sigma(A)\). We need to work out which points on the line are “close” to our points on the circle. Suppose we have a sequence of real numbers \((t_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\) and a point \(p \in [0,2\pi)\) such that the following two conditions are satisfied. Firstly \(| t_n | \rightarrow \infty\) and secondly there exists a sequence of integers \((k_n)_{n \in \mathbb{N}}\) such that \(\lim\limits_{n \to \infty} (t_n – 2\pi k_n) = p\). Then we would have that \(\omega_{t_n}\) converges to \(\nu_p\) in \(\sigma(A)\).

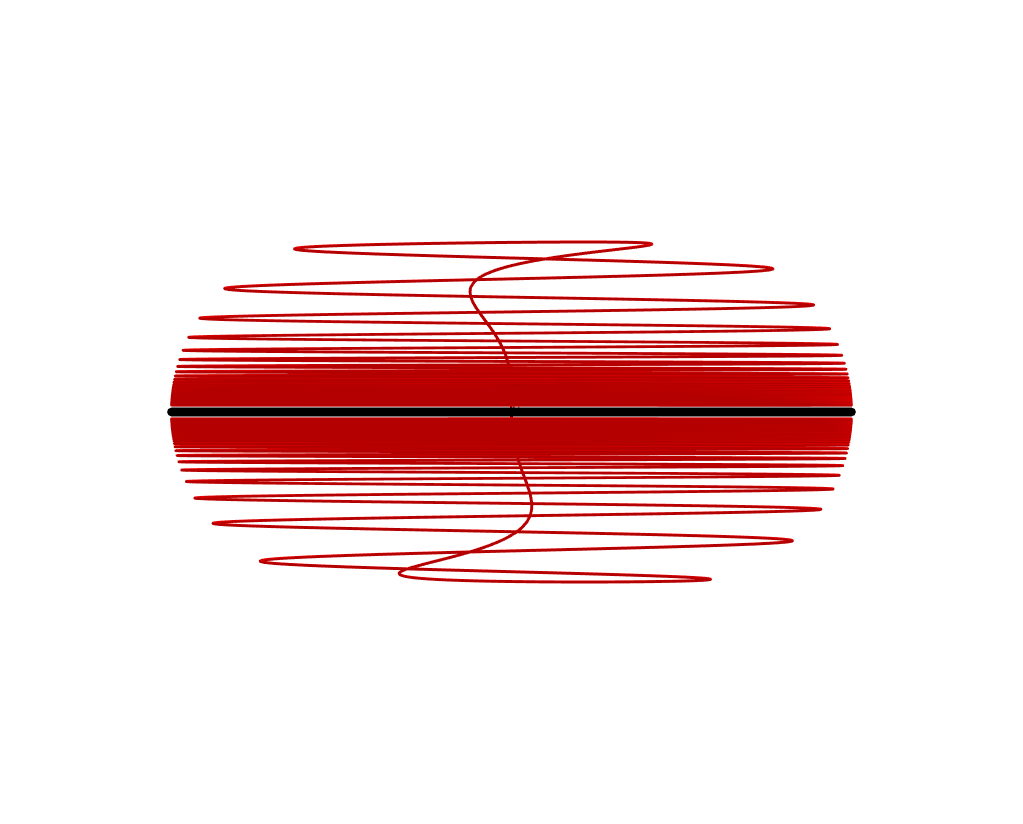

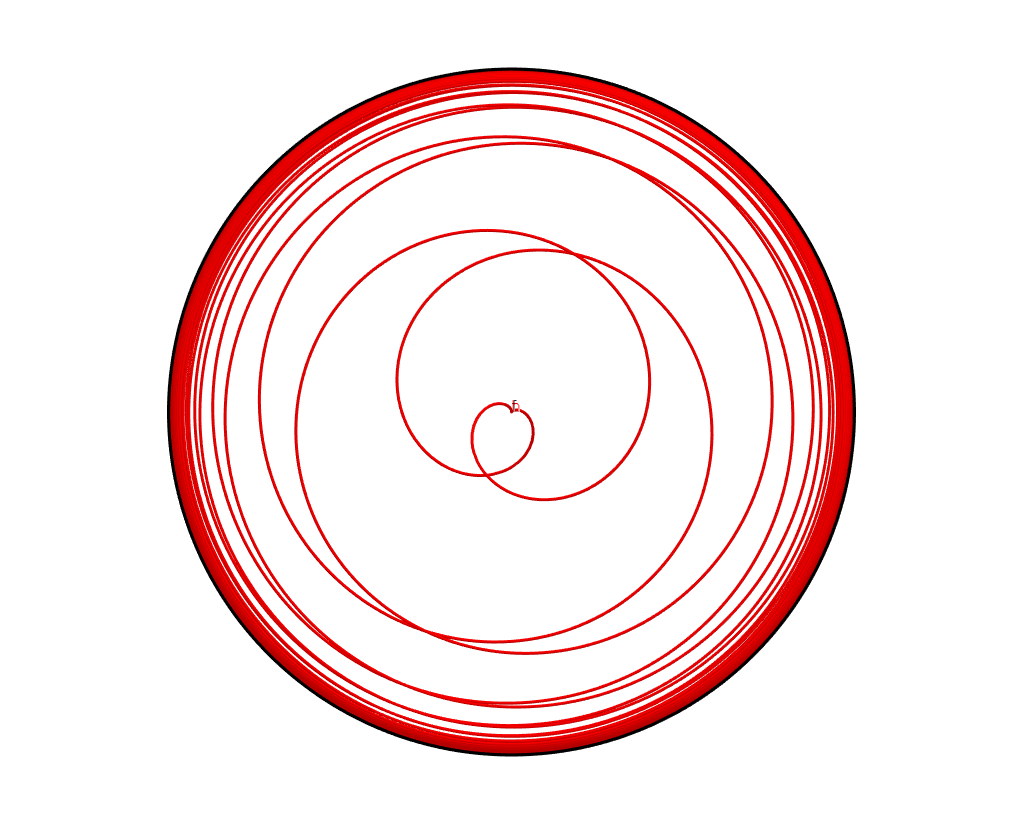

Thus we know that the copy of \(\mathbb{R}\) in must spiral towards the copy of \(S^1\) in \(\sigma(A)\) and that this spiraling must happen as we approach either positive infinity or negative infinity. Thus we can realise \(\sigma(A)\) as the following subset of \(\mathbb{R}^3\) that looks a bit like Christmas tree decoration:

Here we have the black circle sitting in the x,y plane of \(\mathbb{R}^3\). The red line is a copy of \(\mathbb{R}\) that spirals towards the circle. Negative numbers sit below the circle and positive numbers sit above. On left is a sideways view of this space and on the right is the view from above. I made these images in geogebra. If you follow this link, you can see the equations that define the above space and move the space around.

This example shows just how complicated the Stone-Čech compactification \(\beta \mathbb{R}\) of \(\mathbb{R}\) must be. Our relatively simple algebra \(A\) gave this quite complicated compactification shown above. The Stone-Čech compactification surjects onto the above compactification and corresponds to the huge algebra of all bounded and continuous function from \(\mathbb{R}\) to \(\mathbb{C}\).

References

The Wikipedia page on the Stone-Čech compactification and these notes by Terrence Tao were where I first learned of the Stone-Čech compactification. I learnt about C*-algebras in a great course on operator algebras run by James Tenner at ANU. We used the textbook A Short Course on Spectral Theory by William Averson which has some exercises at the end of chapter 2 about the Stone-Čech compactification of \(\mathbb{R}\). The example of the algebra \(A \subseteq C_b(\mathbb{R})\) used in this blog post came from an assignment question set by James.