The singular value decomposition (SVD) is a powerful matrix decomposition. It is used all the time in statistics and numerical linear algebra. The SVD is at the heart of the principal component analysis, it demonstrates what’s going on in ridge regression and it is one way to construct the Moore-Penrose inverse of a matrix. For more SVD love, see the tweets below.

In this post I’ll define the SVD and prove that it always exists. At the end we’ll look at some pictures to better understand what’s going on.

Definition

Let \(X\) be a \(n \times p\) matrix. We will define the singular value decomposition first in the case \(n \ge p\). The SVD consists of three matrix \(U \in \mathbb{R}^{n \times p}, \Sigma \in \mathbb{R}^{p \times p}\) and \(V \in \mathbb{R}^{p \times p}\) such that \(X = U\Sigma V^T\). The matrix \(\Sigma\) is required to be diagonal with non-negative diagonal entries \(\sigma_1 \ge \sigma_2 \ge \ldots \ge \sigma_p \ge 0\). These numbers are called the singular values of \(X\). The matrices \(U\) and \(V\) are required to orthogonal matrices so that \(U^TU=V^TV = I_p\), the \(p \times p\) identity matrix. Note that since \(V\) is square we also have \(VV^T=I_p\) however we won’t have \(UU^T = I_n\) unless \(n = p\).

In the case when \(n \le p\), we can define the SVD of \(X\) in terms of the SVD of \(X^T\). Let \(\widetilde{U} \in \mathbb{R}^{p \times n}, \widetilde{\Sigma} \in \mathbb{R}^{n \times n}\) and \(\widetilde{V} \in \mathbb{R}^{n \times n}\) be the SVD of \(X^T\) so that \(X^T=\widetilde{U}\widetilde{\Sigma}\widetilde{V}^T\). The SVD of \(X\) is then given by transposing both sides of this equation giving \(U = \widetilde{V}, \Sigma = \widetilde{\Sigma}^T=\widetilde{\Sigma}\) and \(V = \widetilde{U}\).

Construction

The SVD of a matrix can be found by iteratively solving an optimisation problem. We will first describe an iterative procedure that produces matrices \(U \in \mathbb{R}^{n \times p}, \Sigma \in \mathbb{R}^{p \times p}\) and \(V \in \mathbb{R}^{p \times p}\). We will then verify that \(U,\Sigma \) and \(V\) satisfy the defining properties of the SVD.

We will construct the matrices \(U\) and \(V\) one column at a time and we will construct the diagonal matrix \(\Sigma\) one entry at a time. To construct the first columns and entries, recall that the matrix \(X\) is really a linear function from \(\mathbb{R}^p\) to \(\mathbb{R}^n\) given by \(v \mapsto Xv\). We can thus define the operator norm of \(X\) via

\(\Vert X \Vert = \sup\left\{ \|Xv\|_2 : \|v\|_2 =1\right\},\)

where \(\|v\|_2\) represents the Euclidean norm of \(v \in \mathbb{R}^p\) and \(\|Xv\|_2\) is the Euclidean norm of \(Xv \in \mathbb{R}^n\). The set of vectors \(\{v \in \mathbb{R} : \|v\|_2 = 1 \}\) is a compact set and the function \(v \mapsto \|Xv\|_2\) is continuous. Thus, the supremum used to define \(\Vert X \Vert\) is achieved at some vector \(v_1 \in \mathbb{R}^p\). Define \(\sigma_1 = \|X v_1\|_2\). If \(\sigma_1 \neq 0\), then define \(u_1 = Xv_1/\sigma_1 \in \mathbb{R}^n\). If \(\sigma_1 = 0\), then define \(u_1\) to be an arbitrary vector in \(\mathbb{R}^n\) with \(\|u\|_2 = 1\). To summarise we have

- \(v_1 \in \mathbb{R}^p\) with \(\|v_1\|_2 = 1\).

- \(\sigma_1 = \|X\| = \|Xv_1\|_2\).

- \(u_1 \in \mathbb{R}^n\) with \(\|u_1\|_2=1\) and \(Xv_1 = \sigma_1u_1\).

We have now started to fill in our SVD. The number \(\sigma_1 \ge 0\) is the first singular value of \(X\) and the vectors \(v_1\) and \(u_1\) will be the first columns of the matrices \(V\) and \(U\) respectively.

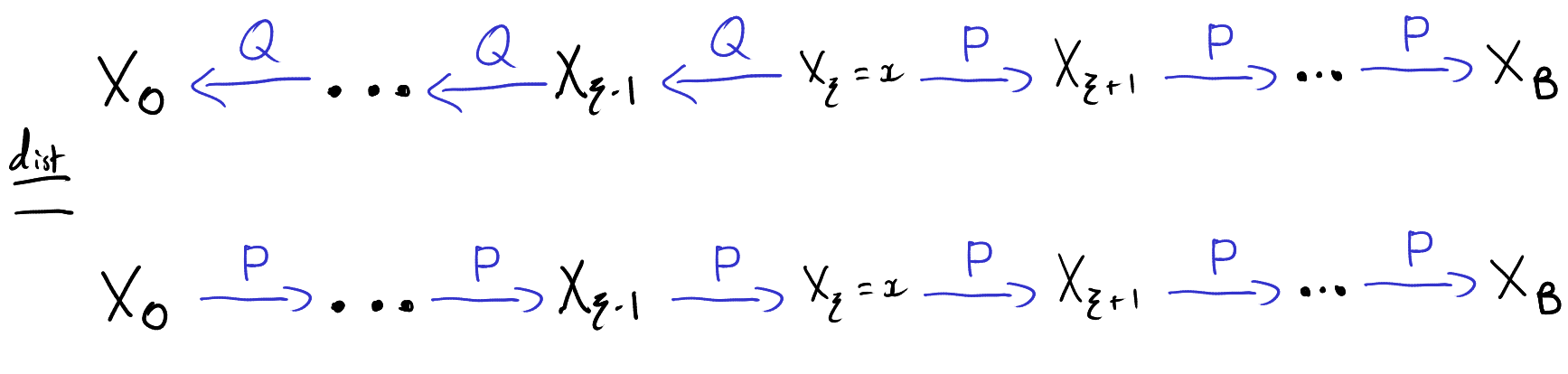

Now suppose that we have found the first \(k\) singular values \(\sigma_1,\ldots,\sigma_k\) and the first \(k\) columns of \(V\) and \(U\). If \(k = p\), then we are done. Otherwise we repeat a similar process.

Let \(v_1,\ldots,v_k\) and \(u_1,\ldots,u_k\) be the first \(k\) columns of \(V\) and \(U\). The vectors \(v_1,\ldots,v_k\) split \(\mathbb{R}^p\) into two subspaces. These subspaces are \(S_1 = \text{span}\{v_1,\ldots,v_k\}\) and \(S_2 = S_1^\perp\), the orthogonal compliment of \(S_1\). By restricting \(X\) to \(S_2\) we get a new linear map \(X_{|S_2} : S_2 \to \mathbb{R}^n\). Like before, the operator norm of \(X_{|S_2}\) is defined to be

\(\|X_{|S_2}\| = \sup\{\|X_{|S_2}v\|_2:v \in S_2, \|v\|_2=1\}\).

Since \(S_2 = \text{span}\{v_1,\ldots,v_k\}^\perp\) we must have

\(\|X_{|S_2}\| = \sup\{\|Xv\|_2:v \in \mathbb{R}^p, \|v\|_2=1, v_j^Tv = 0 \text{ for } j=1,\ldots,k\}.\)

The set \(\{v \in \mathbb{R}^p : \|v\|_2=1, v_j^Tv=0\text{ for } j=1,\ldots,k\}\) is a compact set and thus there exists a vector \(v_{k+1}\) such that \(\|Xv_{k+1}\|_2 = \|X_{|S_2}\|\). As before define \(\sigma_{k+1} = \|Xv_{k+1}\|_2\) and \(u_{k+1} = Xv_{k+1}/\sigma_{k+1}\) if \(\sigma_{k+1}\neq 0\). If \(\sigma_{k+1} = 0\), then define \(u_{k+1}\) to be any vector in \(\mathbb{R}^{n}\) that is orthogonal to \(u_1,u_2,\ldots,u_k\).

This process repeats until eventually \(k = p\) and we have produced matrices \(U \in \mathbb{R}^{n \times p}, \Sigma \in \mathbb{R}^{p \times p}\) and \(V \in \mathbb{R}^{p \times p}\). In the next section, we will argue that these three matrices satisfy the properties of the SVD.

Correctness

The defining properties of the SVD were given at the start of this post. We will see that most of the properties follow immediately from the construction but one of them requires a bit more analysis. Let \(U = [u_1,\ldots,u_p]\), \(\Sigma = \text{diag}(\sigma_1,\ldots,\sigma_p)\) and \(V= [v_1,\ldots,v_p]\) be the output from the above construction.

First note that by construction \(v_1,\ldots, v_p\) are orthogonal since we always had \(v_{k+1} \in \text{span}\{v_1,\ldots,v_k\}^\perp\). It follows that the matrix \(V\) is orthogonal and so \(V^TV=VV^T=I_p\).

The matrix \(\Sigma\) is diagonal by construction. Furthermore, we have that \(\sigma_{k+1} \le \sigma_k\) for every \(k\). This is because both \(\sigma_k\) and \(\sigma_{k+1}\) were defined as maximum value of \(\|Xv\|_2\) over different subsets of \(\mathbb{R}^p\). The subset for \(\sigma_k\) contained the subset for \(\sigma_{k+1}\) and thus \(\sigma_k \ge \sigma_{k+1}\).

We’ll next verify that \(X = U\Sigma V^T\). Since \(V\) is orthogonal, the vectors \(v_1,\ldots,v_p\) form an orthonormal basis for \(\mathbb{R}^p\). It thus suffices to check that \(Xv_k = U\Sigma V^Tv_k\) for \(k = 1,\ldots,p\). Again by the orthogonality of \(V\) we have that \(V^Tv_k = e_k\), the \(k^{th}\) standard basis vector. Thus,

\(U\Sigma V^Tv_k = U\Sigma e_k = U\sigma_k e_k = \sigma_k u_k.\)

Above, we used that \(\Sigma\) was a diagonal matrix and that \(u_k\) is the \(k^{th}\) column of \(U\). If \(\sigma_k \neq 0\), then \(\sigma_k u_k = Xv_k\) by definition. If \(\sigma_k =0\), then \(\|Xv_k\|_2=0\) and so \(Xv_k = 0 = \sigma_ku_k\) also. Thus, in either case, \(U\Sigma V^Tv_k = Xv_k\) and so \(U\Sigma V^T = X\).

The last property we need to verify is that \(U\) is orthogonal. Note that this isn’t obvious. At each stage of the process, we made sure that \(v_{k+1} \in \text{span}\{v_1,\ldots,v_k\}^\perp\). However, in the case that \(\sigma_{k+1} \neq 0\), we simply defined \(u_{k+1} = Xv_{k+1}/\sigma_{k+1}\). It is not clear why this would imply that \(u_{k+1}\) is orthogonal to \(u_1,\ldots,u_k\).

It turns out that a geometric argument is needed to show this. The idea is that if \(u_{k+1}\) was not orthogonal to \(u_j\) for some \(j \le k\), then \(v_j\) couldn’t have been the value that maximises \(\|Xv\|_2\).

Let \(u_{k}\) and \(u_j\) be two columns of \(U\) with \(j < k\) and \(\sigma_j,\sigma_k > 0\). We wish to show that \(u_j^Tu_k = 0\). To show this we will use the fact that \(v_j\) and \(v_k\) are orthonormal and perform “polar-interpolation“. That is, for \(\lambda \in [0,1]\), define

\(v_\lambda = \sqrt{1-\lambda}\cdot v_{j}-\sqrt{\lambda} \cdot v_k.\)

Since \(v_{j}\) and \(v_k\) are orthogonal, we have that

\(\|v_\lambda\|_2^2 = (1-\lambda)\|v_{j}\|_2^2+\lambda\|v_k\|_2^2 = (1-\lambda)+\lambda = 1.\)

Furthermore \(v_\lambda\) is orthogonal to \(v_1,\ldots,v_{j-1}\). Thus, by definition of \(v_j\),

\(\|Xv_\lambda\|_2^2 \le \sigma_j^2 = \|Xv_j\|_2^2.\)

By the linearity of \(X\) and the definitions of \(u_j,u_k\),

\(\|Xv_\lambda\|_2^2 = \|\sqrt{1-\lambda}\cdot Xv_j+\sqrt{\lambda}\cdot Xv_{k+1}\|_2^2 = \|\sigma_j\sqrt{1-\lambda}\cdot u_j+\sigma_{k+1}\sqrt{\lambda}\cdot u_{k+1}\|_2^2\).

Since \(Xv_j = \sigma_ju_j\) and \(Xv_{k+1}=\sigma_{k+1}u_{k+1}\), we have

\((1-\lambda)\sigma_j^2 + 2\sqrt{\lambda(1-\lambda)}\cdot \sigma_1\sigma_2 u_j^Tu_{k}+\lambda\sigma_k^2 = \|Xv_\lambda\|_2^2 \le \sigma_j^2\)

Rearranging and dividing by \(\sqrt{\lambda}\) gives,

\(2\sqrt{1-\lambda}\cdot \sigma_1\sigma_2 u_j^Tu_k \le \sqrt{\lambda}\cdot(\sigma_j^2-\sigma_k^2).\) for all \(\lambda \in (0,1]\)

Taking \(\lambda \searrow 0\) gives \(u_j^Tu_k \le 0\). Performing the same polar interpolation with \(v_\lambda’ = \sqrt{1-\lambda}v_j – \sqrt{\lambda}v_k\) shows that \(-u_j^Tu_k \le 0\) and hence \(u_j^Tu_k = 0\).

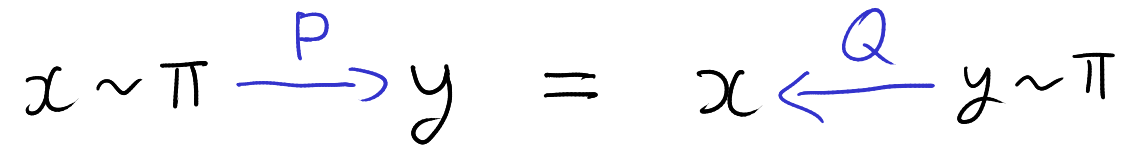

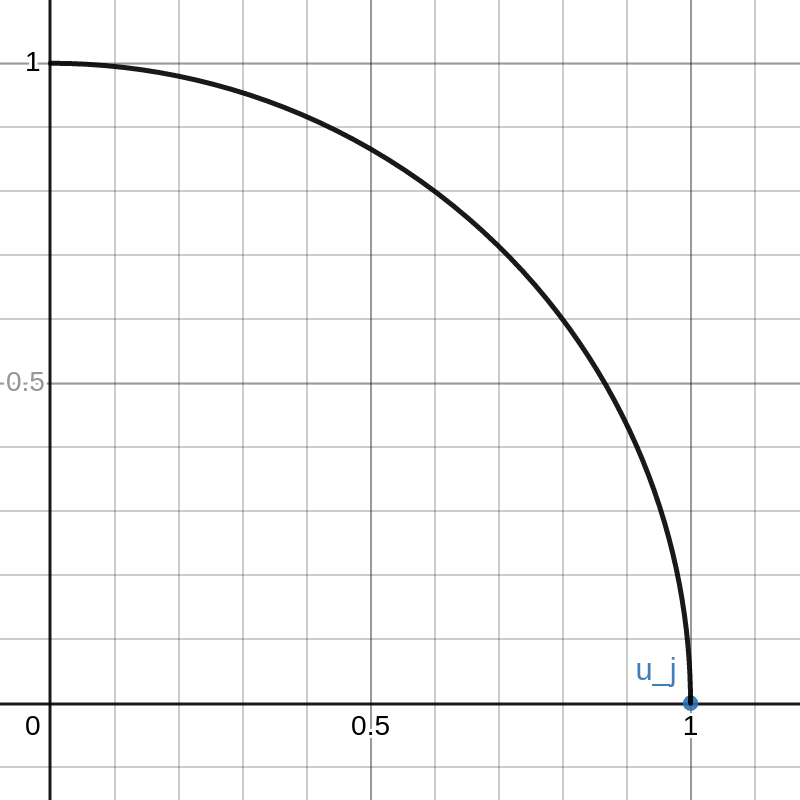

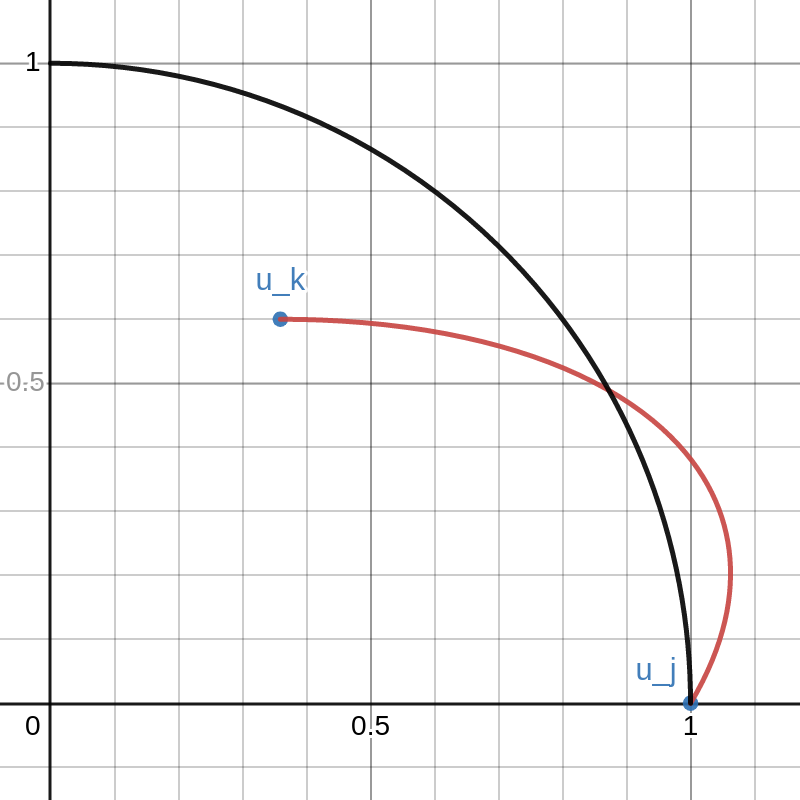

We have thus proved that \(U\) is orthogonal. This proof is pretty “slick” but it isn’t very illuminating. To better demonstrate the concept, I made an interactive Desmos graph that you can access here.

This graph shows example vectors \(u_j, u_k \in \mathbb{R}^2\). The vector \(u_j\) is fixed at \((1,0)\) and a quarter circle of radius \(1\) is drawn. Any vectors \(u\) that are outside this circle have \(\|u\|_2 > 1 = \|u_j\|_2\).

The vector \(u_k\) can be moved around inside this quarter circle. This can be done either cby licking and dragging on the point or changing that values of \(a\) and \(b\) on the left. The red curve is the path of

\(\lambda \mapsto \sqrt{1-\lambda}\cdot u_j+\sqrt{\lambda}\cdot u_k\).

As \(\lambda\) goes from \(0\) to \(1\), the path travels from \(u_j\) to \(u_k\).

Note that there is a portion of the red curve near \(u_j\) that is outside the black circle. This corresponds to a small value of \(\lambda > 0\) that results in \(\|X v_\lambda\|_2 > \|Xv_j\|_2\) contradicting the definition of \(v_j\). By moving the point \(u_k\) around in the plot you can see that this always happens unless \(u_k\) lies exactly on the y-axis. That is, unless \(u_k\) is orthogonal to \(u_j\).