The 2025 World Jigsaw Puzzle Championship recently took place in Spain. In the individual heats, competitors had to choose their puzzle. Each competitor could either complete a 500-piece rectangular puzzle or a 500-piece circular puzzle. For example, in Round F, puzzlers could choose one of the following two puzzles:

There are many things to consider when picking a puzzle. First, the puzzles had already been released. This meant a puzzler could get an advantage by choosing to do a puzzle they had already completed. The image on the puzzle is also important, as is the puzzle’s style. In the example above, most puzzlers picked the circular puzzle because it had a clear colour gradient and distinct sections.

The commentators mentioned that puzzlers might also consider the number of edge pieces. The circular puzzles have fewer edge pieces than the rectangular puzzles. This could make the rectangular puzzle easier because some puzzlers like to do the edge first and then build inwards.

The difference in edge pieces isn’t a coincidence. Circular puzzles have fewer edge pieces than any other 500-piece puzzle. This fact is a consequence of a piece of mathematics called the isoperimetric inequality.

The isopermetric inequality

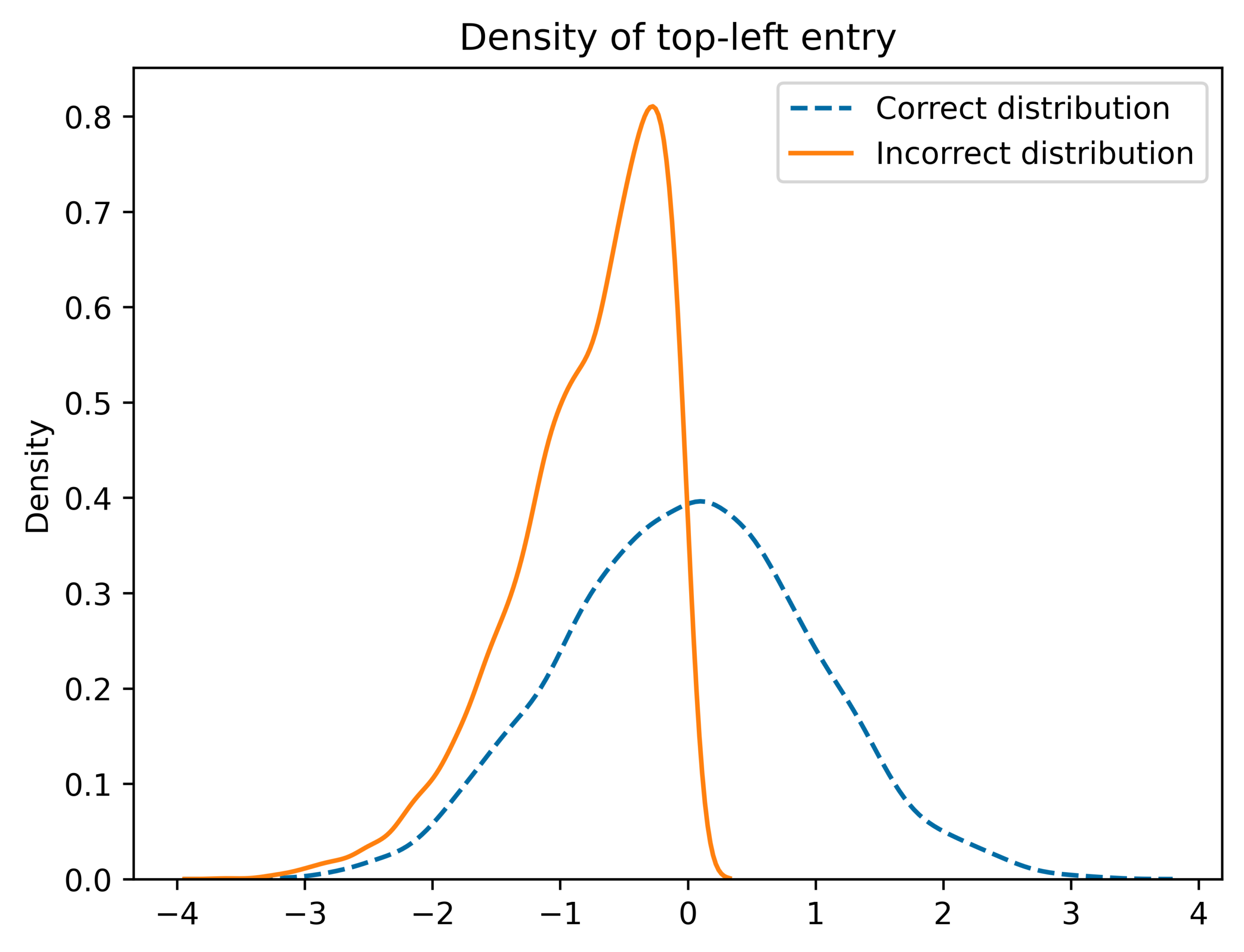

The isoperimetric inequality is a statement about 2D shapes. The word ‘isoperimetric’ literally translates to ‘having the same perimeter.’ The isoperimetric inequality says that if a shape has the same perimeter as a particular circle, then the circle has a larger (or equal) area. For example, the square and circle below have the same perimeter but the circle has a larger area:

The isoperimetric inequality can also be flipped around to give a statement about shapes with the same area. This ‘having the same area’ inequality states that if a shape has the same area as a circle, then the circle has a smaller (or equal) perimeter. For example, the square and circle below have the same area but the circle has a smaller perimeter:

The ‘having the same area’ inequality applies to the jigsaw puzzles above. In a jigsaw puzzle, the area is proportional to the number of pieces and the perimeter is proportional to the number of edge pieces (assuming the pieces are all roughly the same size and shape). This means that if one puzzle has the same number of pieces as a circular puzzle (for example 500), then the circular puzzle will have fewer edge pieces! This is exactly what the commentator said about the puzzles in the competition!

I don’t think many of the puzzlers thought about the isopermetric inequality when picking their puzzles. But if you ever do a circular puzzle, remember that you’re doing a puzzle with as few edge pieces as possible!