I recently gave a talk on the Yang-Baxter equation. The focus of the talk was to state the connection between the Yang-Baxter equation and the braid relation. This connection comes from a system of interacting particles. In this post, I’ll go over part of my talk. You can access the full set of notes here.

Interacting particles

Imagine two particles on a line, each with a state that can be any element of a set \(\mathcal{X}\). Suppose that the only way particles can change their states is by interacting with each other. An interaction occurs when two particles pass by each other. We could define a function \(F : \mathcal{X} \times \mathcal{X} \to \mathcal{X} \times \mathcal{X}\) that describes how the states change after interaction. Specifically, if the first particle is in state \(x\) and the second particle is in state \(y\), then their states after interacting will be

\(F(x,y) = (F_a(x,y), F_b(x,y)) = (\text{new state of particle 1}, \text{new state of particle 2}), \)

where \(F_a,F_b : \mathcal{X} \times \mathcal{X} \to \mathcal{X}\) are the components of \(F\). Recall that the particles move past each other when they interact. Thus, to keep track of the whole system we need an element of \(\mathcal{X} \times \mathcal{X}\) to keep track of the states and a permutation \(\sigma \in S_2\) to keep track of the positions.

Three particles

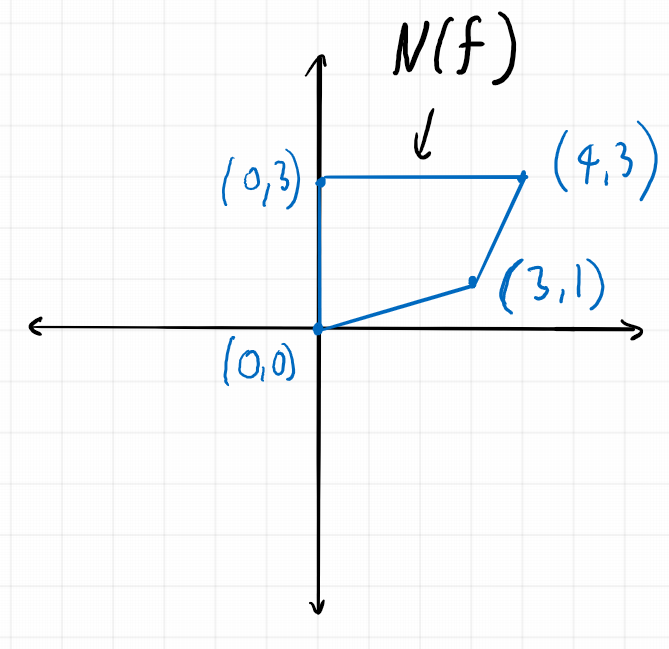

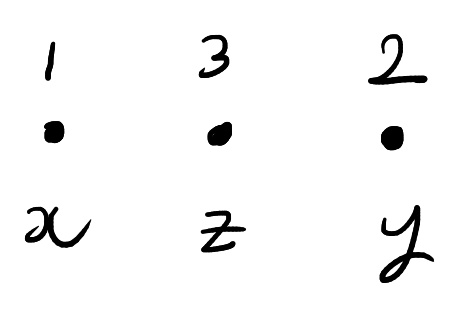

Now suppose that we have \(3\) particles labelled \(1,2,3\). As before, each particle has a state in \(\mathcal{X}\). We can thus keep track of the state of each particle with an element of \(\mathcal{X}^3\). The particles also have a position which is described by a permutation \(\sigma \in S_3\). The order the entries of \((x,y,z) \in \mathcal{X}^3\) corresponds to the labels of the particles not their positions. A possible configuration is shown below:

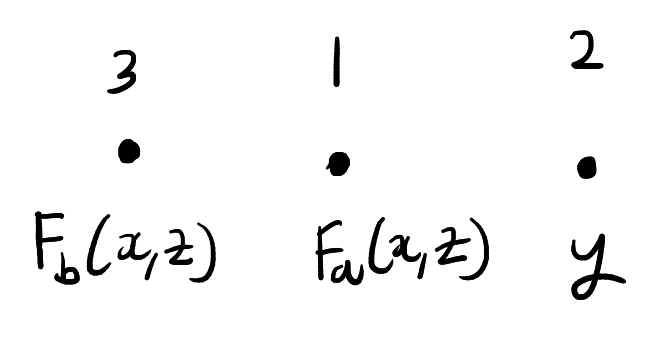

As before, the particles can interact with each other. However, we’ll now add the restriction that the particles can only interact two at a time and interacting particles must have adjacent positions. When two particles interact, they swap positions and their states change according to \(F\). The state and position of the remaining particle is unchanged. For example, in the above picture we could interact particles \(1\) and \(3\). This will produce the below configuration:

To keep track of how the states of the particles change over time we will introduce three functions from \(\mathcal{X}^3\) to \(\mathcal{X}^3\). These functions are \(F_{12},F_{13},F_{23}\). The function \(F_{ij}\) is given by applying \(F\) to the \(i,j\) coordinates of \((x,y,z)\) and acting by the identity on the remaining coordinate. In symbols,

\(F_{12}(x,y,z) = (F_a(x,y), F_b(x,y), z),\)

\(F_{13}(x,y,z) = (F_a(x,z), y, F_b(x,z)),\)

\(F_{23}(x,y,z) = (x, F_a(y,z), F_b(y,z)).\)

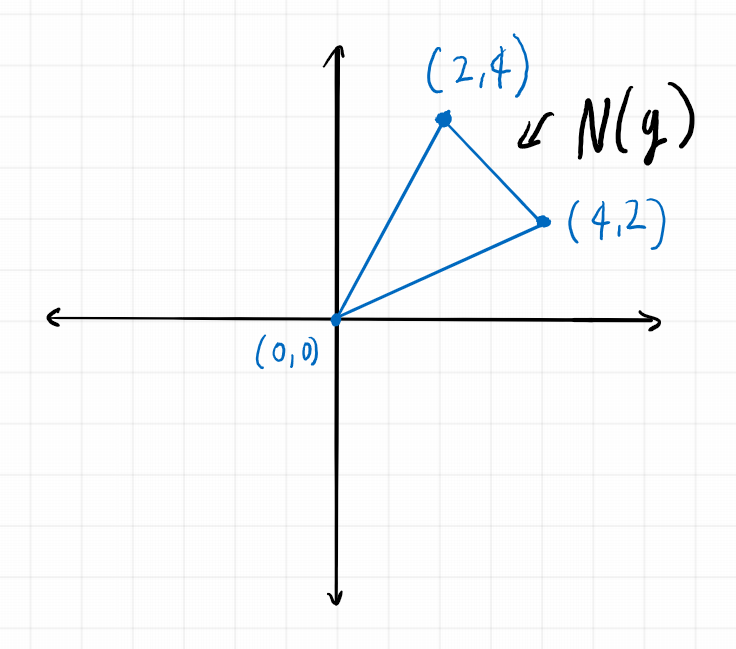

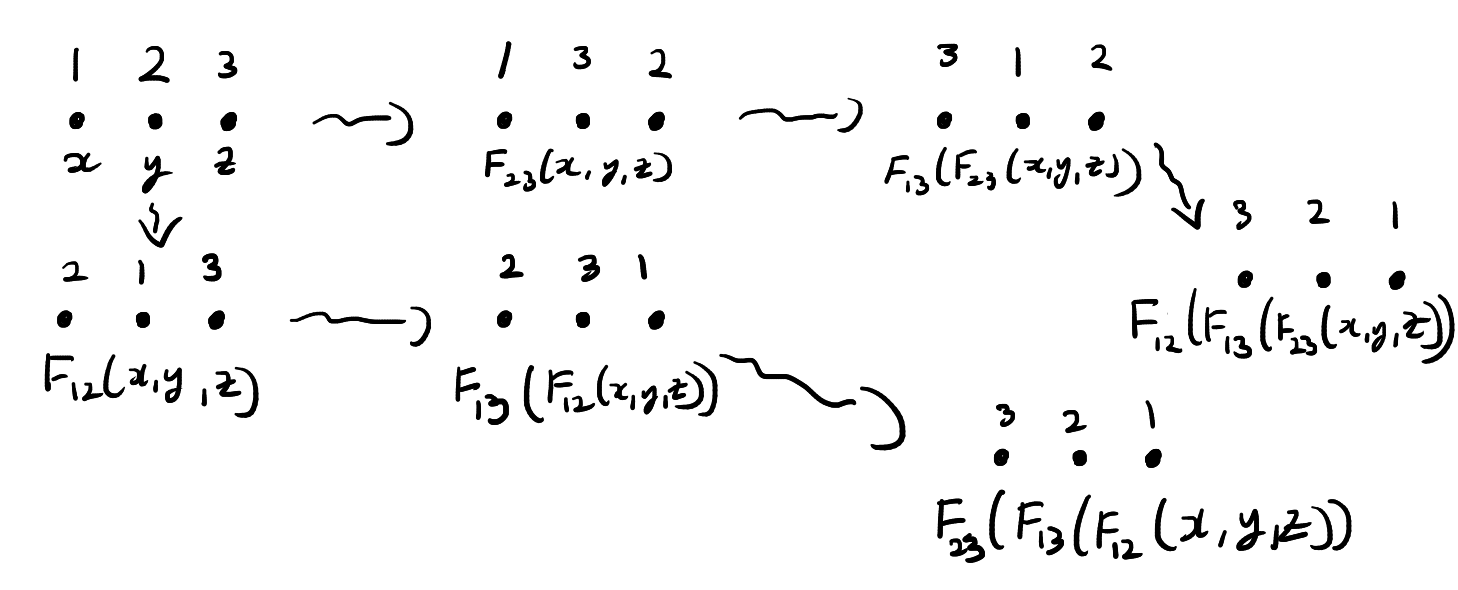

The function \(F_{ij}\) exactly describes how the states of the three particles change when particles \(i\) and \(j\) interact. Now suppose that three particles begin in position \(123\) and states \((x,y,z)\). We cannot directly interact particles \(1\) and \(3\) since they are not adjacent. We have to pass first pass one of the particles through particle \(2\). This means that there are two ways we can interact particles \(1\) and \(3\). These are illustrated below.

In the top chain of interactions, we first interact particles \(2\) and \(3\). In this chain of interactions, the states evolve as follows:

\((x,y,z) \to F_{23}(x,y,z) \to F_{13}(F_{23}(x,y,z)) \to F_{12}(F_{13}(F_{23}(x,y,z))).\)

In the bottom chain of interactions, we first interact particles \(1\) and \(2\). On this chain, the states evolve in a different way:

\((x,y,z) \to F_{12}(x,y,z) \to F_{13}(F_{12}(x,y,z)) \to F_{23}(F_{13}(F_{12}(x,y,z))).\)

Note that after both of these chains of interactions the particles are in position \(321\). The function \(F\) is said to solve the Yang–Baxter equation if two chains of interactions also result in the same states.

Definition: A function \(F : \mathcal{X} \times \mathcal{X} \to \mathcal{X} \times \mathcal{X}\) is a solution to the set theoretic Yang–Baxter equation if,

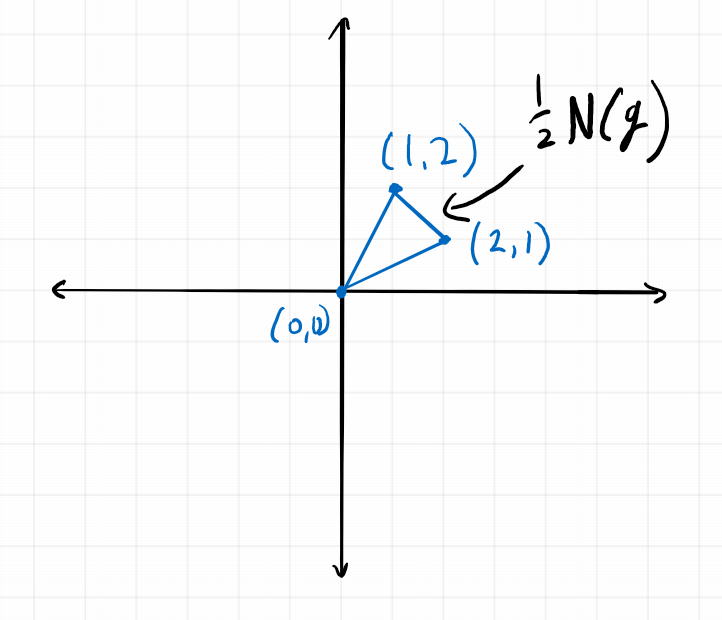

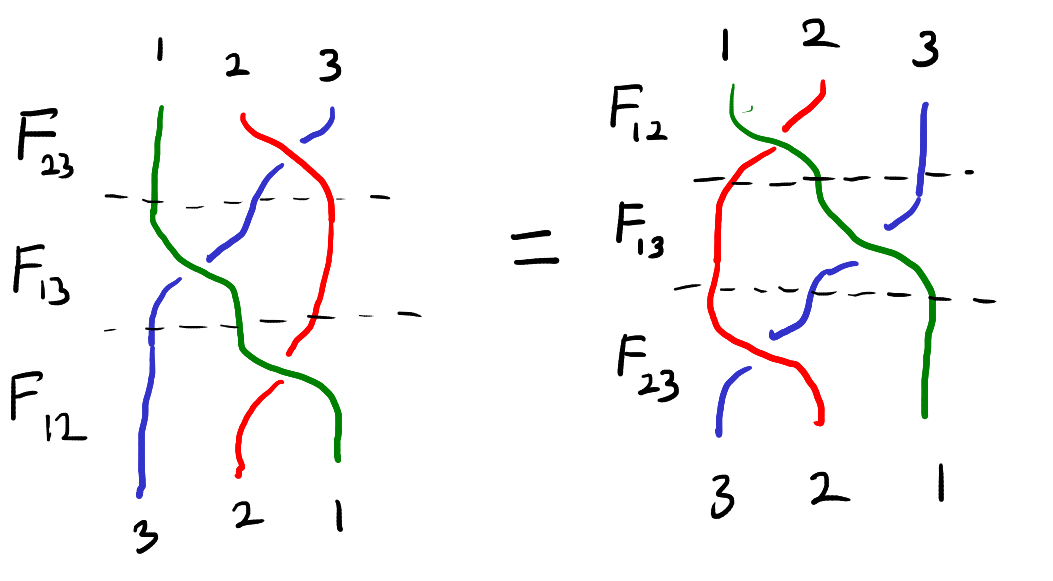

\(F_{12}\circ F_{13} \circ F_{23} = F_{23} \circ F_{13} \circ F_{12}. \)

This equation can be visualized as the “braid relation” shown below. Here the strings represent the three particles and interacting two particles corresponds to crossing one string over the other.

Here are some examples of solutions to the set theoretic Yang-Baxter equation,

- The identity on \(\mathcal{X} \times \mathcal{X}\).

- The swap map, \((x,y) \mapsto (y,x)\).

- If \(f,g : \mathcal{X} \to \mathcal{X}\) commute, then the function \((x,y) \to (f(x), g(y))\) is a solution the Yang-Baxter equation.

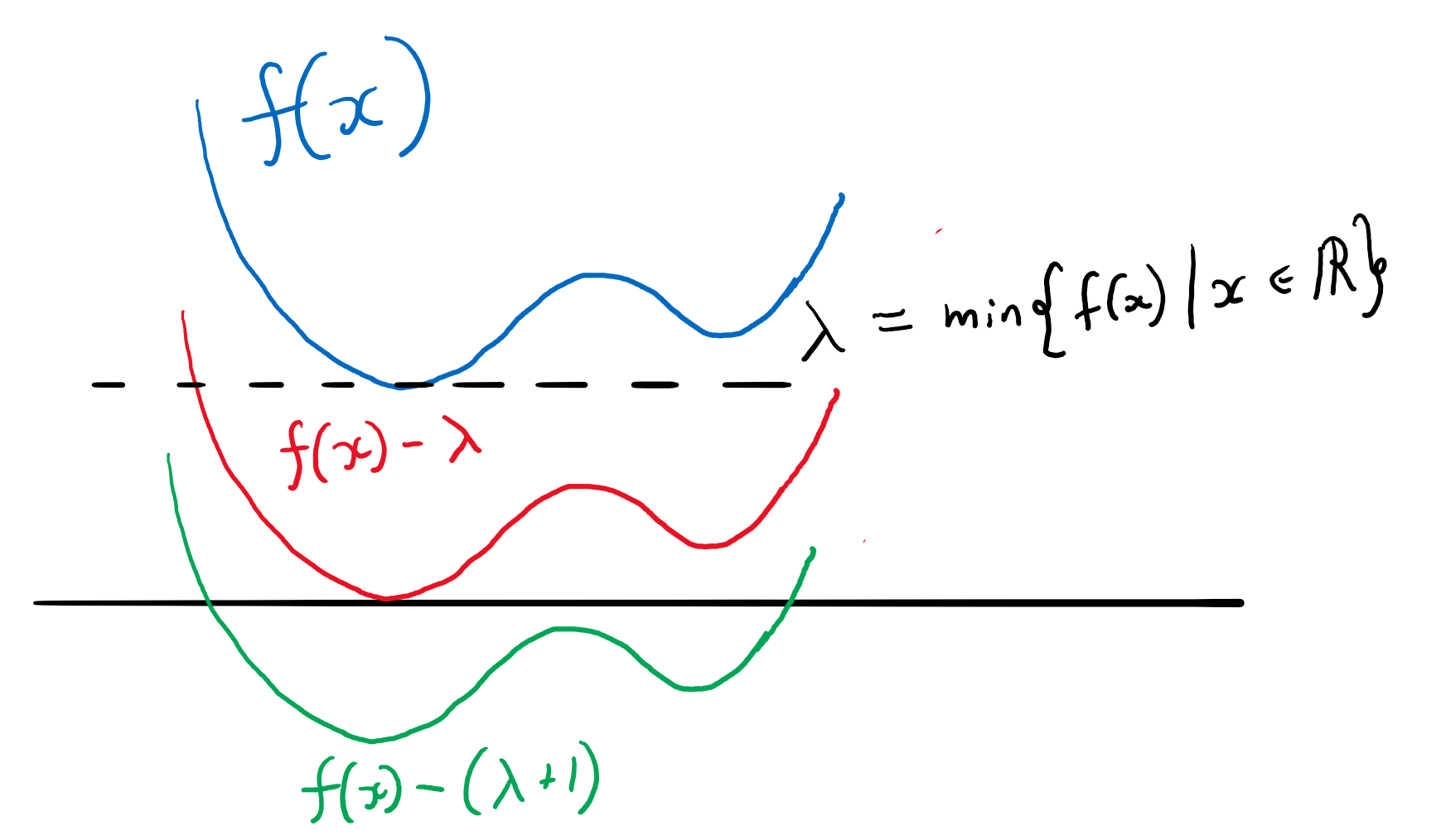

In the full set of notes I talk about a number of extensions and variations of the Yang-Baxter equation. These include having more than three particles, allowing for the particle states to be entangle and the parametric Yang-Baxter equation.