I am very excited to be writing a blog post again – it has been nearly a year! This post marks a new era for the blog. In September I started a statistics PhD at Stanford University. I am really enjoying my classes and I am learning a lot. I might have to change the name of the blog soon but for now let’s stick with “Maths to Share” although you will undoubtedly see more and more statistics here.

Today I would like to talk about leverages scores. Leverages scores are a way to quantify how sensitive a model is and they can be used to explain the different behaviour in these two animations

Linear Models

I recently learnt about leverage scores in the applied statistics course STATS 305A. This course is all about the linear model. In the linear model we assume with have \(n\) data points \((x_i,y_i)\) where \(x_i\) is a vector in \(\mathbb{R}^d\) and \(y_i\) is a number in \(\mathbb{R}\). We model \(y_i\) as a linear function of \(x_i\) plus noise. That is we assume \(y_i = x_i^T\beta + \varepsilon_i\), where \(\beta \in \mathbb{R}^d\) is a unknown vector of coefficients and \(\varepsilon_i\) is a random variable with mean \(0\) and variance \(\sigma^2\). We also require that for \(i \neq j\), the random variable \(\varepsilon_i\) is uncorrelated with \(\varepsilon_j\).

We can also write this as a matrix equation. Define \(y\) to be the vector with entries \(y_i\) and define \(X\) to be the matrix with rows \(x_i^T\), that is

\(y = \begin{bmatrix} y_1\\ y_2 \\ \vdots \\ y_n \end{bmatrix} \in \mathbb{R}^n\) and \(X = \begin{bmatrix} -x_1^T-\\-x_2^T-\\ \vdots \\ -x_n^T-\end{bmatrix} \in \mathbb{R}^{n \times d}.\)

Then our model can be rewritten as

\(y = X\beta + \varepsilon,\)

where \(\varepsilon \in \mathbb{R}^n\) is a random vector with mean \(0\) and covariance matrix \(\sigma^2 I_n\). To simplify calculations we will assume that \(X\) contains an intercept term. This means that the first column of \(X\) consists of all 1’s.

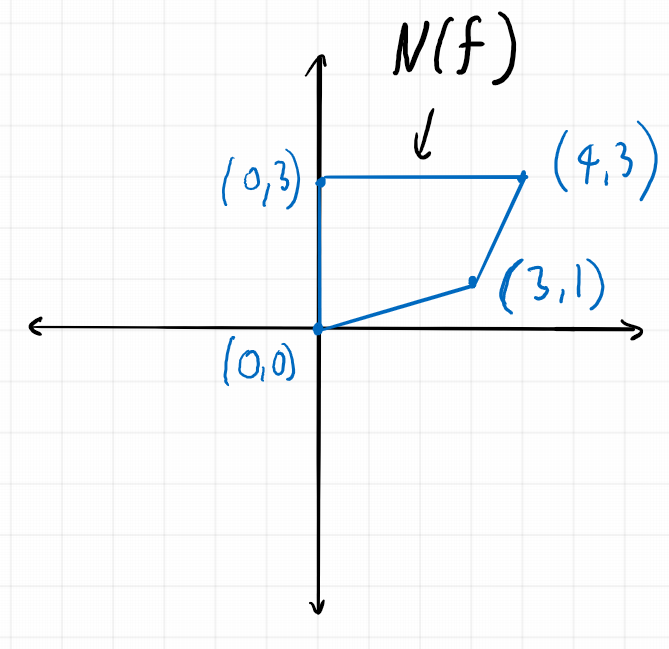

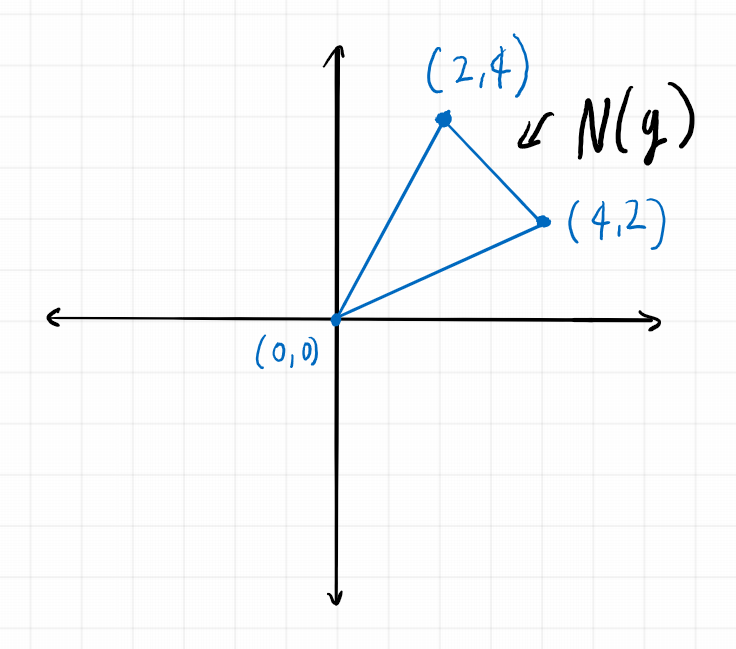

In the two animations at the start of this post we have two nearly identical data sets. The data sets are an example of simple regression when each vector \(x_i\) is of the form \((1,z_i)\) where \(z_i\) is a number. The values \(z_i\) are on the horizontal axis and the values \(y_i\) are on the vertical axis.

Estimating the coefficients

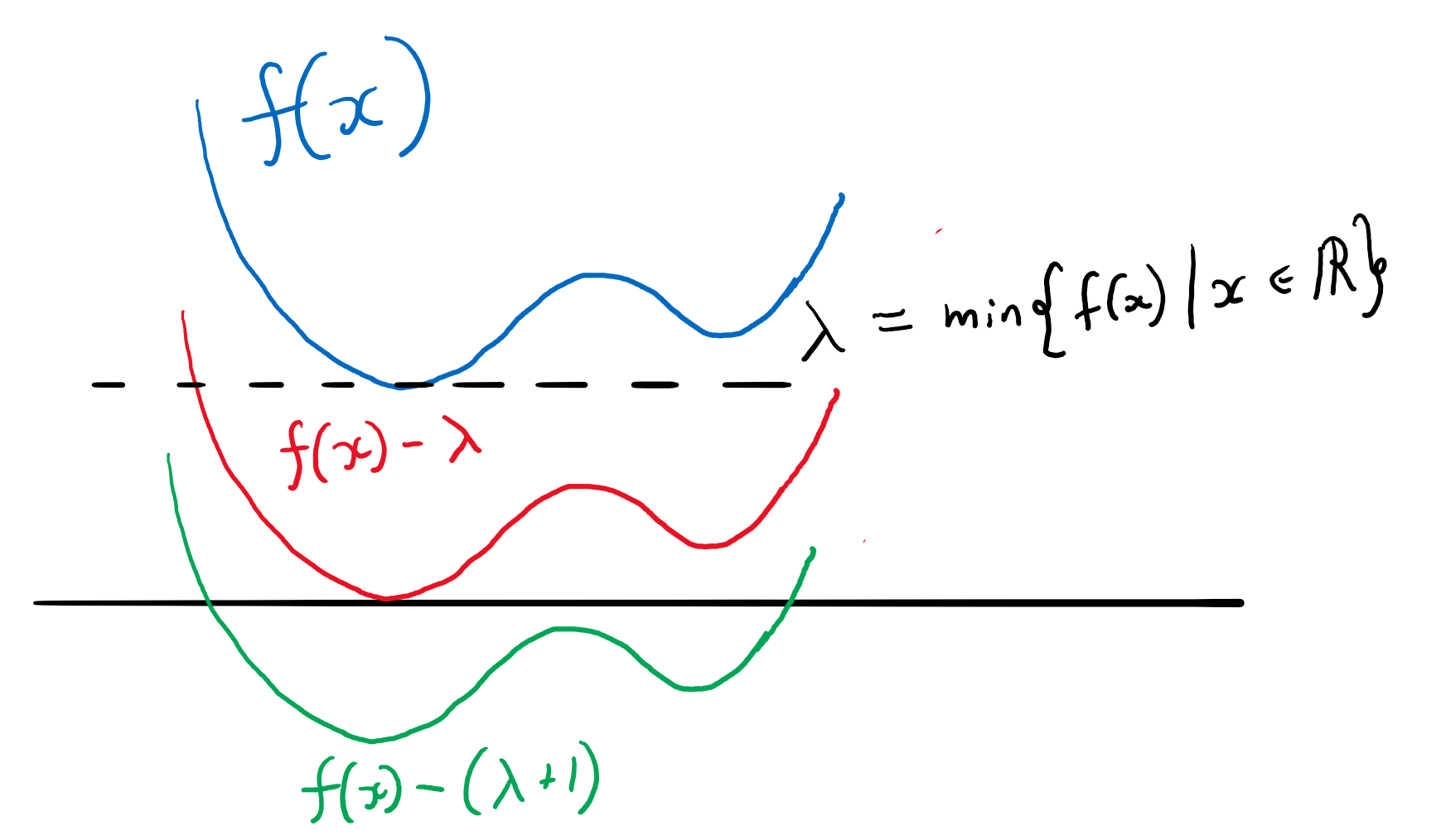

In the linear model we wish to estimate the parameter \(\beta\) which contains the coefficients of our model. That is, given a sample \((y_i,x_i)_{i=1}^n\), we wish to construct a vector \(\widehat{\beta}\) which approximates the true parameter \(\beta\). In ordinary least square regression we choose \(\widehat{\beta}\) to be the vector \(b \in \mathbb{R}^d\) that minimizes the quantity

\(\sum_{i=1}^n (x_i^T b – y_i)^2=\left \Vert Xb – y \right \Vert_2^2\).

Differentiating with respect to \(b\) and setting the derivative equal to \(0\) shows that \(\widehat{\beta}\) is a solution to the normal equations:

\(X^TXb = X^T y.\)

We will assume that the matrix \(X^TX\) is invertible. In this case then the normal equations have a unique solution \(\widehat{\beta} = (X^TX)^{-1}X^T y\).

Now that we have our estimate \(\widehat{\beta}\), we can do prediction. If we are given a new value \(x’ \in \mathbb{R}^d\) we would use \(x’^T\widehat{\beta}\) to predict the corresponding value of \(y’\). This was how the straight lines in the two animations were calculated.

We can also calculate the model’s predicted values for the data \(x_i\) that we used to fit the model. These are denoted by \(\widehat{y}\). Note that

\(\widehat{y} = X\widehat{\beta} = X(X^TX)^{-1}X^Ty = Hy,\)

where \(H = X(X^TX)^{-1}X^T\) is called the hat matrix for the model (since it puts the hat \(\widehat{ }\) on \(y\).

Leverage scores

We are now ready to talk about leverage scores and the two animations. For reference, here they are again:

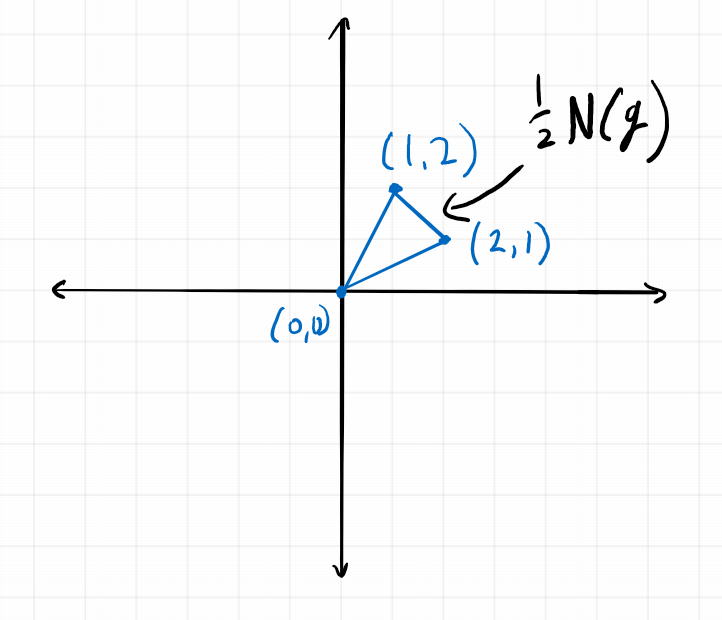

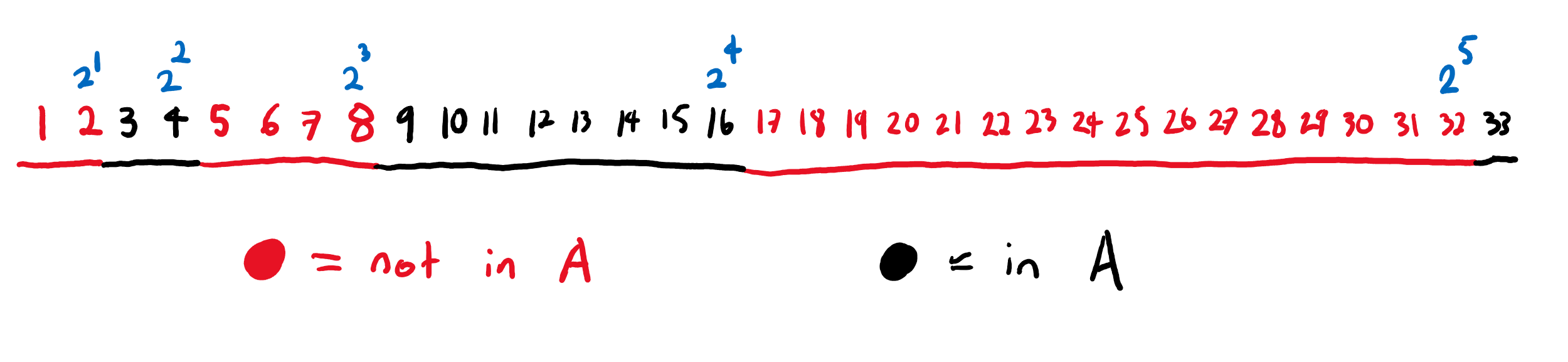

In both animations the stationary line corresponds to an estimator \(\widehat{\beta}\) that was calculated using only the black data points. The red points are new data points with different \(x\) values and varying \(y\) values. The moving line corresponds to an estimator \(\widehat{\beta}\) calculated using the red data point as well as all the black points. We can see immediately that if the red point is far away from the “bulk” of the other \(x\) points, then the moving line is a lot more sensitive to the \(y\) value of the red point.

The leverage score of a data point \((x_i,y_i)\) is defined to be \(\frac{\partial \widehat{y}_i}{\partial y_i}.\) That is, the leverage score tells us how much does the prediction \(\widehat{y}_i\) change if we change \(y_i\).

Since \(\widehat{y} = Hy\), the leverage score of \((x_i,y_i)\) is \(H_{ii}\), the \(i^{th}\) diagonal element of the hat matrix \(H\). The idea is that if a data point \((x_i,y_i)\) has a large leverage score, then the model is more sensitive to changes in that value of \(y_i\).

This can be seen in a leave one out calculation. This calculation tells us what we should expect if we make a leave-one-out model – a model that uses all the data points apart from one. In our animations, this corresponds to the stationary line.

The leave one out calculation says that the predicted value using all the data is always between the true value and the predicted value from the leave-one-out model. In our animations this can be seen by noting that the moving line (the full model) is always between the red point (the true value) and the stationary line (the leave-one-out model).

Furthermore the leverage score tells us exactly how close the predicted value is to the true value. We can see that the moving line is much closer to the red dot in the high leverage example on the right than the low leverage example on the left.

Mahalanobis distance

We now know that the two animations are showing the sensitivity of a model to two different data points. We know that a model is more sensitive to point with high leverage than to points with low leverage. We still haven’t spoken about why some point have higher leverage and why the point on the right has higher leverage.

It turns out that leverage score are measuring how far away a data point is from the “bulk” of the other \(x_i\)’s. More specifically in a one dimensional example like what we have in the animations

\(H_{ii} = \frac{1}{n}\left(\frac{1}{S^2}(x_i-\bar{x})^2+1\right),\)

where \(n\) is the number of data points, \(\bar{x} = \frac{1}{n}\sum_{j=1}^n x_j\) is the sample mean and \(S^2 = \frac{1}{n}\sum_{j=1}^n (x_j-\bar{x})^2\) is the sample variance. Thus high leverage scores correspond to points that are far away from the centre of our data \(x_i\). In higher dimensions a similar result holds if we measure distance using Mahalanobis distance.

The mean of the black data points is approximately 2 and so we can now see why the second point has higher leverage. The two animations were made in Geogebra. You can play around with them here and here.